One of the pushbacks I get from time to time when discussing FBI/CIA/NSA stuff, like yesterday's Trump performance of running directly against the intel community's findings on Russia (bad), North Korea (not disarming), Iran (not so bad) is that the intel folks got 2003 wrong.

Um, not quite and what they got wrong was partly on Hussein. Huh? First, there were a lot of reports before the war. The intel community did not have a consensus that there was a nuclear weapons program in Iraq. What mattered was that there were enough hints and rumors that a motivated person could extract those and make a case for a WMD program that needed to be attacked. Oh, and that person was Dick Cheney. He cherry-picked the intel to find the stuff he wanted to find. In my interactions with military folks, they like to say that intel drives policy--that the info drives what the country/unit should do. In the case of 2003, it was very clearly the case that policy--we need to attack Iraq--drove intel: "hey, lookie, this says that there might be a chance Hussein is pursuing WMD!"

Moreoever, Hussein did little to dissuade folks because his strategies to both stay in power and deter the neighbors. That is, Hussein created heaps of ambiguity about the weapons programs inside the country, with many military officials wondering mid-war why these capabilities were not being deployed, so that potential opponents within Iraq would be frightened of him. Likewise, after the failed war with Iran and other foreign misdventures, he wanted to deter the outsiders. Of course, it was a dumb move since aspiring to develop WMD puts a target on one's country. The point is that the confusion in 2003 about what Iraq was doing was partially intended by Hussein.

The intel community might have gotten wrong how fragile Iraq was, that it would be hard to govern after an invasion--I am not sure about that since it has gotten less coverage. But the intel about WMD was gamed by the White House and Rummy's shop and not by the CIA or NSA.

Sure, folks were upset about what the NSA has been doing thanks to Snowden. And, yes, the FBI has not been a force for social justice. So, none of these agencies have been loved by Liberals and those further to the left. However, those who want a sensible foreign policy tend to want to have functional intel agencies--knowing more about the world is usually conducive to better policy. As it turns out, the intel agencies, despite much efforts by the Trump administration to politicize them, are still mostly reality based organizations who have clearer eyes about what Russia/China/North Korea/Iran are doing. That their reports are dismissed by Trump is a tell--that he would rather do what he wants rather than what the US national interest happens to be. Trump does not like folks to disagree with him, but disagreeing with the intel agencies is inevitable if one is deliberately and inherently ignorant.

This leads to a strange dynamic where the enemy of my enemy is my friend, so Liberals have reduced their criticism of the intel agencies despite the FBI leaking to the GOP about HRC and on and on and have embraced these organizations, even has they have done much that is not so nice in the past (and present). For me, this is where I tend to be more centrist--that foreign policy requires secrets, requires trying to read the mail of the adversaries, and even sometimes requires subversion and violence.

Anyhow, this is a longer post than intended. The key is this: 2003 is not a good way to de-legitimate the secret squirrels who are putting out reports in 2019. It is a good way to to criticize the GOP, which has been the party of ignorance for more than just the Trump administration. The difference is now it is not in service of a convoluted view of the national interest but is an effort to reduce Trump's vulnerability to prosecution.

International Relations, Ethnic Conflict, Civil-Military Relations, Academia, Politics in General, Selected Silliness

Pages

▼

Wednesday, January 30, 2019

Sunday, January 27, 2019

Conference Strategery: Banffing It Up

After the conference in Calgary, I drove to Banff, which serves as a base area for my forays into the mountains--skiing, that is--at Lake Louise. As with everything, it was a learning experience. I shall listicle since that seems to be my twitter tendency this week.

I was here last year, again due to an academic trip to Calgary. I didn't see much of the mountain or the views last time since it was snowing heavily. This time? Beautiful:

- Flat light is bad when there is clumpy snow. I ended up having a few spills as I slammed into some unexpected snow clumps.

- There is a reason we have chair lifts--the old alternatives sucked mightily. I took a "platter" (seemed like a j-bar) to me up the highest peak. I wanted to do one of the winding back of the mountain routes. Which leads to the next lesson.

- Trailed named boomerang will.

- Chocolate milk remains superior to hot chocolate as the apres-ski beverage unless it is super cold and it was not.

- When one is tired enough to nearly fall asleep on the chair lift, it is time to quit.

- No need to let ego get in the way--many green (less advanced) runs can be much fun. Lake Louise, like Whistler, has a bunch of fun green runs. I spent most of the day on blue runs, but the greens were fun. I didn't ski on any black runs, as I didn't run across any that were bumpless. No moguls for this guy's knees.

- Banff has much to offer as well. Lots of good restaurants, much souvenir shopping, some history as the local hot springs helped generate Canada's first national park, and, yes, more beautiful mountains.

I was here last year, again due to an academic trip to Calgary. I didn't see much of the mountain or the views last time since it was snowing heavily. This time? Beautiful:

As a friend of mine put it, I live a charmed life. That I can do side trips like this is so very fortunate. While my listicle might seen like a bit of whining, I really appreciate where my life is now.

As Joe Walsh has said,

Saturday, January 26, 2019

The State of Canadian Defence and Security Studies

I was in Calgary the past couple of days for a conference on the State of Canadian Defence and Security Studies. There were profs from across Canada, some grad students, reps from the Journal of Military and Strategic Studies, and some folks from relevant funding agencies. Because it was a Chatham House Rules event, I can't cite what individuals said (other than me, of course, see below), but I can give the general gist.

And, well, the mood was fairly grim. Why? Because there is not much hiring these days and not much university support for defence and security stuff. History departments long ago moved away from hiring military historians. Poli sci? Depends. The challenge is that those who focus on Canada are limiting their own careers as work on Canada tends not to published outside of Canada and tends not to get cited. If cites and publishing in top journals are the ways to get ahead, departments may not hire those who choose to write on Canada. Oh, and the end of the Security and Defence Forum about seven years ago hurt the regeneration of the Canadian defence and security community.

I was not so grim for a couple of reasons. First, Carleton and NPSIA has built defence/security as a key strength--there have been new positions created (mine, for one) and retirements/departures have been replaced. Second, I think there is a pathway to getting good pubs and cites for those who study Canada: either compare with other cases or work with others elsewhere. The basic reality is that most folks are disinterested not just in Canada but in many countries--there are few countries that are viewed by many as intrinsically interesting--US, Russia, China and a few others. So, scholars of Australia or Belgium or many others are more likely to publish more visible work in partnership. This may not work for other people, and it may be a product of my biases--I have always engaged in comparative work. Third, there is the CDSN.

I presented the status of the Canadian Defence and Security Network. There is a defence and security community, but it is like a body without a nervous system or skeleton. The CDSN would help energize the community, work with a variety of partners, and build the next generation. So, let me talk through the slides I presented.

The CDSN builds on but does not replicate the old SDF research centers, adding units from schools that were not involved before and CIRRIQC (a Quebec network that didn't exist in the old days). The members include not just political scientists and historians but also sociologists, psychologists, and folks from yet other disciplines. We have had government agencies involved all along the way, with members of the leadership team including a defence scientist and a prof from the Canadian Forces College. We have involved non-gvernmental organizations and think tanks interested in defence/security. We include groups that will improve our ability to involve women (WIIS-Canada) and, well, Bridge the Gap between academics and policy-types. We have also built on our individual networks to connect to institutions in the US and Europe.

What do we seek to do? To build a network--so that scholars and elements of civil society and the government know what research is being done, what questions folks want answered, and foster teamwork within and across various divides. To share data so that there is less duplication and we get more bang for our research buck. To engage the public so that the citizens understand better this critical sector. And, yes, to regenerate but do so in ways that are more inclusive.

How? We have five themes to serve as focal points: defence procurement, personnel issues, operations, civil-military relations and security. Each one will have annual workshops that will focus on specific issues. For instance, the personnel group will focus in the first three years (if we are funded, more on that below) on how to reduce discrimination against women in the Canadian Armed Forces. The civil-military relations node will focus on using surveys (with Nanos (and analysis of social media to assess how the media shapes attitudes and knowledge of the forces. If funded, we w

ill connect students at all levels with the various CDSN efforts, mentoring, training and giving them fora to present their work. And, yes, connect to the network. It turns out that there are summer institutes on defence/security so our idea is not that original except our aim is to include not just younger academics but also policy officers and military officers--to give each varying perspectives from the other sectors while getting drinking from the firehose of knowledge from the profs in the network. I'll save the Capital Capstone idea for now.

Where do we go from here? Well, we will know soon whether we will be funded by SSHRC. If so, then we are off to the races. We will also throw our hats into the next DND network grant competition (one bit of news from this conference is that we don't know when that competition will be, so the "this winter" may be spring?).

What challenges do we face? Some may not want academics to interact with the armed forces. I think we have handled that well by not including defence contractors in the partnership and by bringing in groups from civil society who are known to be critical of the CAF and DND. One challenge is that we don't look new because we have been working at it for five or so years.

My presentation was well-received, so we shall see. I feel pretty good about the CDSN's chances. So, that is a key reason why I don't feel grim. That and I drove today to Banff so that I can ski tomorrow!

And, well, the mood was fairly grim. Why? Because there is not much hiring these days and not much university support for defence and security stuff. History departments long ago moved away from hiring military historians. Poli sci? Depends. The challenge is that those who focus on Canada are limiting their own careers as work on Canada tends not to published outside of Canada and tends not to get cited. If cites and publishing in top journals are the ways to get ahead, departments may not hire those who choose to write on Canada. Oh, and the end of the Security and Defence Forum about seven years ago hurt the regeneration of the Canadian defence and security community.

I was not so grim for a couple of reasons. First, Carleton and NPSIA has built defence/security as a key strength--there have been new positions created (mine, for one) and retirements/departures have been replaced. Second, I think there is a pathway to getting good pubs and cites for those who study Canada: either compare with other cases or work with others elsewhere. The basic reality is that most folks are disinterested not just in Canada but in many countries--there are few countries that are viewed by many as intrinsically interesting--US, Russia, China and a few others. So, scholars of Australia or Belgium or many others are more likely to publish more visible work in partnership. This may not work for other people, and it may be a product of my biases--I have always engaged in comparative work. Third, there is the CDSN.

I presented the status of the Canadian Defence and Security Network. There is a defence and security community, but it is like a body without a nervous system or skeleton. The CDSN would help energize the community, work with a variety of partners, and build the next generation. So, let me talk through the slides I presented.

The CDSN builds on but does not replicate the old SDF research centers, adding units from schools that were not involved before and CIRRIQC (a Quebec network that didn't exist in the old days). The members include not just political scientists and historians but also sociologists, psychologists, and folks from yet other disciplines. We have had government agencies involved all along the way, with members of the leadership team including a defence scientist and a prof from the Canadian Forces College. We have involved non-gvernmental organizations and think tanks interested in defence/security. We include groups that will improve our ability to involve women (WIIS-Canada) and, well, Bridge the Gap between academics and policy-types. We have also built on our individual networks to connect to institutions in the US and Europe.

What do we seek to do? To build a network--so that scholars and elements of civil society and the government know what research is being done, what questions folks want answered, and foster teamwork within and across various divides. To share data so that there is less duplication and we get more bang for our research buck. To engage the public so that the citizens understand better this critical sector. And, yes, to regenerate but do so in ways that are more inclusive.

How? We have five themes to serve as focal points: defence procurement, personnel issues, operations, civil-military relations and security. Each one will have annual workshops that will focus on specific issues. For instance, the personnel group will focus in the first three years (if we are funded, more on that below) on how to reduce discrimination against women in the Canadian Armed Forces. The civil-military relations node will focus on using surveys (with Nanos (and analysis of social media to assess how the media shapes attitudes and knowledge of the forces. If funded, we w

ill connect students at all levels with the various CDSN efforts, mentoring, training and giving them fora to present their work. And, yes, connect to the network. It turns out that there are summer institutes on defence/security so our idea is not that original except our aim is to include not just younger academics but also policy officers and military officers--to give each varying perspectives from the other sectors while getting drinking from the firehose of knowledge from the profs in the network. I'll save the Capital Capstone idea for now.

Where do we go from here? Well, we will know soon whether we will be funded by SSHRC. If so, then we are off to the races. We will also throw our hats into the next DND network grant competition (one bit of news from this conference is that we don't know when that competition will be, so the "this winter" may be spring?).

What challenges do we face? Some may not want academics to interact with the armed forces. I think we have handled that well by not including defence contractors in the partnership and by bringing in groups from civil society who are known to be critical of the CAF and DND. One challenge is that we don't look new because we have been working at it for five or so years.

My presentation was well-received, so we shall see. I feel pretty good about the CDSN's chances. So, that is a key reason why I don't feel grim. That and I drove today to Banff so that I can ski tomorrow!

Wednesday, January 23, 2019

Bullies in the Field of IR

When I posted the other day about Bullies in IR, I was referring to leaders/countries making threats hoping to cow others into submission. The IR scholars on my facebook page thought I was going to discuss bullies in the field of IR and were disappointed that I did not. Are there bullies in our field? Absolutely. Should I out the ones that I have observed? Um, I don't know. Yes, there are still costs, even to a full professor, to antagonizing those who wield power in ways that are cruel and abusive, as they might target my students, for instance. There were bullies in each of the departments I have worked, but their impact varied depending on how the larger community reacted. In some places, they were contained/constrained, and, in others, they were empowered.

What kinds of bullying are there? Senior folks picking on junior faculty (I have heard about one sending unsolicited tenure letters to sink the candidacies of scholars elsewhere), majority folks (white, male, etc) picking on less represented groups, profs abusing their power over students (including but not only sexual harassment), profs abusing their staff, etc. Things can work, of course, in the opposite direction, but since power plays a role in much of this, bullying the more powerful seems unsustainable to me.

What motivates bullying? The obvious answer is insecurity, but people can try to push others around for all kinds of reasons--because they enjoy it, because they get stuff out of it, because they have been trained to do so, etc. Impunity certainly plays a role--why change your behavior if there are no consequences?

The problem, of course, is that bullies are successful in creating climates of fear--that they are not outed because people worry that they will face retaliation directly or indirectly by the person or by their friends. Yes, I was willing to out a sexual harasser because I knew the case very well and, well, I knew that he had limited ability to harm me, so it was not so brave.

Some might suggest developing reporting mechanisms that allow for anonymous complaints so that the bully can't target those who blow the whistle. However, anonymity is problematic since it can be used not just to report bullying but to do bullying (see Political Science Rumors and its predecessors).

Within a department, one should be able to find allies to organize collective action (always easier in smaller groups). But that collective action won't go very far if the administration is not interested in improving things. And, yes, administrators may care less about bullying and more about how much money a person brings in or how often their work is cited. I wonder about the incentive structures not just of bullies but those in administrative positions.

Perhaps the most feasible solution in the short term in the profession is rather than calling out the bad actors is to call out the good ones. #academickindness and #scholarsunday and other twitter threads dedicated to identifying the positive influences, the kind people, the non-bullies, may help create positive environments and norms, and provide less space, less implied tolerance of bullying. At least, that is the easiest collective action we can do. As administrators, as convenors of meetings, as hiring committees, and in our other roles, we can reward kindness and punish bullying. Why invite an asshole to one's edited volume project or to one's conference? It is beyond me when I see a particular bully hired again and again. At some point, the reputation should become clear and that people ought not hire such folks even if their work is highly cited. When bullies get to be named President of an association, I am appalled. Can't we do better? Can't we include decency as a criteria?

I have spent far more time studying the role of power in international relations than the role of power and the behavior of bullies in academia, so I am out of ideas. What ideas do folks have?

What kinds of bullying are there? Senior folks picking on junior faculty (I have heard about one sending unsolicited tenure letters to sink the candidacies of scholars elsewhere), majority folks (white, male, etc) picking on less represented groups, profs abusing their power over students (including but not only sexual harassment), profs abusing their staff, etc. Things can work, of course, in the opposite direction, but since power plays a role in much of this, bullying the more powerful seems unsustainable to me.

What motivates bullying? The obvious answer is insecurity, but people can try to push others around for all kinds of reasons--because they enjoy it, because they get stuff out of it, because they have been trained to do so, etc. Impunity certainly plays a role--why change your behavior if there are no consequences?

The problem, of course, is that bullies are successful in creating climates of fear--that they are not outed because people worry that they will face retaliation directly or indirectly by the person or by their friends. Yes, I was willing to out a sexual harasser because I knew the case very well and, well, I knew that he had limited ability to harm me, so it was not so brave.

Some might suggest developing reporting mechanisms that allow for anonymous complaints so that the bully can't target those who blow the whistle. However, anonymity is problematic since it can be used not just to report bullying but to do bullying (see Political Science Rumors and its predecessors).

Within a department, one should be able to find allies to organize collective action (always easier in smaller groups). But that collective action won't go very far if the administration is not interested in improving things. And, yes, administrators may care less about bullying and more about how much money a person brings in or how often their work is cited. I wonder about the incentive structures not just of bullies but those in administrative positions.

Perhaps the most feasible solution in the short term in the profession is rather than calling out the bad actors is to call out the good ones. #academickindness and #scholarsunday and other twitter threads dedicated to identifying the positive influences, the kind people, the non-bullies, may help create positive environments and norms, and provide less space, less implied tolerance of bullying. At least, that is the easiest collective action we can do. As administrators, as convenors of meetings, as hiring committees, and in our other roles, we can reward kindness and punish bullying. Why invite an asshole to one's edited volume project or to one's conference? It is beyond me when I see a particular bully hired again and again. At some point, the reputation should become clear and that people ought not hire such folks even if their work is highly cited. When bullies get to be named President of an association, I am appalled. Can't we do better? Can't we include decency as a criteria?

I have spent far more time studying the role of power in international relations than the role of power and the behavior of bullies in academia, so I am out of ideas. What ideas do folks have?

Monday, January 21, 2019

The Rise of the Bullies and IR Theory

The past few years challenge much of the conventional understanding of international relations. One of the big lessons from the IR scholarship of the 1970s is that the nature of international relations is that threats and bullying don't work. As Robert Jervis discussed it, the world can be either a constant chicken game or a repeated prisoner's dilemma--aka deterrence vs. spiral model. In short, is international relations an environment (a system!) where countries cave into threats or do they balance against them, that those who believe that pushing countries around are usually confronting with coalitions created by such bullying. Kaiser Wilhelm, as IR scholars use as a example, threatened everyone, hoping that they would back down. Instead, these countries solidified their alliances and showed up in Europe in August 1914. Oops.

Over the past several years, we have seen a series of countries engage in bullying behavior--Russia, Saudi Arabia, Trump's US and China. Russia has wielded nuclear threats to encourage Europeans to not deploy troops to the Baltics and to dissuade them from supporting Ukraine. How has that worked so far? Saudi Arabia has seemingly become unhinged as of late, overreacting to Canadian discussions of Saudi human rights and all but warring upon Qatar. Trump, well, is a bully, so we ought not be surprised by his threats nor by his ignorance of IR scholarship. Threatening the allies has led them to ponder hedging and alternatives. He might think the North Koreans have submitted after last year's threats, but I am pretty sure the North Koreans think they have the upper hand.

The big surprise, to me anyway, is China. China has managed its rise so very well in large part because it has mostly wielded a velvet fist. Yes, it has buzzed American planes and ships, had friction with Indonesia, and other stuff. But generally, the China of the 2000s and early 2010s has been replaced by a more aggressive and obnoxious China. The tiff with Canada is important since Canada was the western democracy least likely to object to the Huawei company getting inside Canada's 5G. Well, not any more. The current standoff is causing Canadian parties to rally against China--who is arguing now that Canada should submit? Moreover, a conversation with a European diplomat today reminded me that Canada has more influence than folks think. Not necessarily to push China back into the straight and narrow but to serve as bellwether. If a country has a problem with the US or EU, well, those are powerful entities that can antagonize. But a country has a problem with Canada? That suggests that the particular country is problematic... and, jeez, is China problematic these days.

I am not a China expert so I don't really know what is driving China to behave this way. I would guess domestic politics and nationalism (populism? Not quite). But everything I have learned in my career tells me that China's choices now are self-destructive--that being aggressive does not pay in the long run. That bullying is counter-productive. Perhaps China is encouraged because the US led by Trump is so incompetent and unreliable, which means balancing will be late, inept and weak. But it is still a dumb move--the Chinese have been gaining strength with little opposition because they were not overly aggressive.

The thing about IR theory stuff--it didn't say that bullying didn't happen. It just said it was not productive. So, the question for future IR scholars, if we live so long, is whether China, Russia, Saudi Arabia and Trump's US are punished or not. We shall see.

Over the past several years, we have seen a series of countries engage in bullying behavior--Russia, Saudi Arabia, Trump's US and China. Russia has wielded nuclear threats to encourage Europeans to not deploy troops to the Baltics and to dissuade them from supporting Ukraine. How has that worked so far? Saudi Arabia has seemingly become unhinged as of late, overreacting to Canadian discussions of Saudi human rights and all but warring upon Qatar. Trump, well, is a bully, so we ought not be surprised by his threats nor by his ignorance of IR scholarship. Threatening the allies has led them to ponder hedging and alternatives. He might think the North Koreans have submitted after last year's threats, but I am pretty sure the North Koreans think they have the upper hand.

The big surprise, to me anyway, is China. China has managed its rise so very well in large part because it has mostly wielded a velvet fist. Yes, it has buzzed American planes and ships, had friction with Indonesia, and other stuff. But generally, the China of the 2000s and early 2010s has been replaced by a more aggressive and obnoxious China. The tiff with Canada is important since Canada was the western democracy least likely to object to the Huawei company getting inside Canada's 5G. Well, not any more. The current standoff is causing Canadian parties to rally against China--who is arguing now that Canada should submit? Moreover, a conversation with a European diplomat today reminded me that Canada has more influence than folks think. Not necessarily to push China back into the straight and narrow but to serve as bellwether. If a country has a problem with the US or EU, well, those are powerful entities that can antagonize. But a country has a problem with Canada? That suggests that the particular country is problematic... and, jeez, is China problematic these days.

I am not a China expert so I don't really know what is driving China to behave this way. I would guess domestic politics and nationalism (populism? Not quite). But everything I have learned in my career tells me that China's choices now are self-destructive--that being aggressive does not pay in the long run. That bullying is counter-productive. Perhaps China is encouraged because the US led by Trump is so incompetent and unreliable, which means balancing will be late, inept and weak. But it is still a dumb move--the Chinese have been gaining strength with little opposition because they were not overly aggressive.

The thing about IR theory stuff--it didn't say that bullying didn't happen. It just said it was not productive. So, the question for future IR scholars, if we live so long, is whether China, Russia, Saudi Arabia and Trump's US are punished or not. We shall see.

Friday, January 18, 2019

Not Gonna Happen, Explained

Every couple of weeks, one of my colleagues at NPSIA, an economist, asks me, "Come on, Steve, are you still so sure Trump will not be impeached?" (Caveat: I got 2016 wrong, so what do I know?) We had that conversation again yesterday. I wish I could just flash this thing I created at him

To be clear, there are a few stages to the impeachment process: the House of Representatives considers one or more articles (charges) of impeachment (you can bet on multiple articles); then the House votes and a majority of yea's sends it to the Senate. So, when folks say a President has been impeached, they might mean just this part of the process, and, if so, my meme above doesn't apply. However, there is the next stage, where the Senate holds a trial and then the entire Senate acts as jury, with a 2/3s vote needed to convict. My meme above refers to that--don't count on Trump losing his office due to impeachment precisely because I don't think that 67 Senators will vote to impeach.

Let me explain. I have changed my mind about the first stage. The latest revelations--that Trump directed his lawyer (and probably others) to lie to Congress--are definitely impeachable. As someone on twitter reminded me, the first article against Nixon was exactly this. I am sure that the Mueller report will contain enough stuff that it will be hard, if not impossible, for the Democrats in the House to avoid voting on impeachment. Nancy Pelosi can count votes, and I am pretty sure she will get a heap of pressure by much of the party to put impeachment articles on the agenda.

It comes down to this--Trump is only leaving the White House in six ways (in increasing order of likelihood):

To be clear, there are a few stages to the impeachment process: the House of Representatives considers one or more articles (charges) of impeachment (you can bet on multiple articles); then the House votes and a majority of yea's sends it to the Senate. So, when folks say a President has been impeached, they might mean just this part of the process, and, if so, my meme above doesn't apply. However, there is the next stage, where the Senate holds a trial and then the entire Senate acts as jury, with a 2/3s vote needed to convict. My meme above refers to that--don't count on Trump losing his office due to impeachment precisely because I don't think that 67 Senators will vote to impeach.

Let me explain. I have changed my mind about the first stage. The latest revelations--that Trump directed his lawyer (and probably others) to lie to Congress--are definitely impeachable. As someone on twitter reminded me, the first article against Nixon was exactly this. I am sure that the Mueller report will contain enough stuff that it will be hard, if not impossible, for the Democrats in the House to avoid voting on impeachment. Nancy Pelosi can count votes, and I am pretty sure she will get a heap of pressure by much of the party to put impeachment articles on the agenda.

Quick tangent: why wouldn't Pelosi want to have Trump impeached? Because she and other Dems think they would be in the same position as the 1998 Republicans who got smacked pretty hard for trying to impeach Clinton. I think this is different--that Trump has proven to be unfit to a majority of Americans. Yes, his base will be pissed and turn out more in 2020. However, this will also energize the Democratic base, and, since turnout is a Democratic problem and there are more Democrats than Republicans, and since Trump is not appealing to independents either, I don't think this is 1998. I am guessing Pelosi will agree eventually.So, I think impeachment in terms of the first stage will happen. But here's the thing--if they can't even get 60 Senators to keep sanctions on Russian companies linked to Putin, how will an impeachment vote get 67 votes? Keeping sanctions on the Russians is EASY--no one's base is demanding the reduction of sanctions on the Russians yet the GOP, including the supposed voice of moderation Mitt Romney, held the line. FFS. So, no, the President will not be impeached. Nor will he be 25th Amendment-ed, as that would require his cabinet to turn against him and then getting a super-majority vote through the Senate (and House).

It comes down to this--Trump is only leaving the White House in six ways (in increasing order of likelihood):

- Trump loses the primaries to another Republican. Fun to imagine, not going to happen. The GOP is his party now, and a large chunk, the most likely to show up at a primary election are a bunch of cultists.

- Trump quits. One could imagine him making a deal where he and his family get to keep their ill-gotten gains and go free but leave office. I doubt it, since he has been trained to think being President gives him immunity and allows him to pardon anyone he wants. And why should he not believe these things.

- Trump is impeached as the GOP in the Senate realize that their states actually contain a good number of folks who have been hurt by Trump's policies (these policies tend to hurt GOP voters but not GOP donors).

- Trump leaves at the end of his second term.

- Trump has a heart attack, stroke, or other medical problem that either kills him or permits 25th amendment to be applied.

- Trump is defeated by a Democratic candidate in 2020. This is the only path that Democrats can really count on. Trump can still win, of course, but this the one where Democratic activism, effort, donations, organization, etc can make a difference. The Dems can't make the Republican Senators value country over party, but they can do their damnedest to turn out and win.

Wednesday, January 16, 2019

Civil Oversight? Lessons from Belgium and New Zealand

Yesterday, a piece co-authored by Phil Lagassé and myself hit the streets. Ok, it was moved from "early view" to actually published. Woot! Phil wrote a blog post to celebrate to explain what he did (his fieldwork, my title)*:

When Civilian Oversight is 'Civil': Parliamentary

Oversight of the Military in Belgium and New Zealand

In October of 2016, Russia accused the Belgian air

force of killing civilians in Syria. In many political systems, this might

cause the opposition to attack the government either because they feel betrayed

by the government’s secrecy or because it is an opportunity to score

points. Instead, Belgium’s secret-cleared

parliamentary committee overseeing military operations met, sufficient

information was provided to prove that the Russian accusation was baseless, and

the opposition was then satisfied. What

could have been a conflict within Belgian politics and perhaps a civil-military

confrontation was quickly defused. This

was possible because Belgium has a cooperative form of civilian oversight of

its armed forces. We find a similar type

of cooperative oversight in New Zealand. Drawing on principal-agent theory,

which identifies two types of oversight --police patrols and fire alarms-- our

study argues that Belgium and New Zealand use a third type of oversight to

scrutinize their military affairs: community policing (Steve says: because we need more metaphors!)

Existing principal-agent studies note that principals,

such as legislatures, use 'active police patrols' or 'reactive fire alarms' to hold

agents, such as executives, to account. Police patrols and fire alarms tend to

rest on suspicion and confrontation toward the agent by the principal.

Community policing, on the other hand, refers to oversight that emphasizes a

comparatively higher degree of trust and collaboration between the principal

and the agent. The aim of community policing is not to detect the agent's misbehaviour

through intrusive measures or alerts, but to satisfy the principal’s concerns

that the agent is being transparent and to assure the agent that the principal

respects their autonomy in return. Rather than stressing confrontation,

community policing relies more on confidence-building between the principal and

agent.

Our paper argues

that oversight operates along a spectrum of trust (Table 1):

Table

1. Trust and Oversight Strategies

|

Trust

|

High

|

Moderate

|

Low

|

|

Form

of Oversight

|

Community Policing

|

Fire Alarms

|

Police Patrols

|

The higher the trust between the principal and the

agent, the more likely that a community policing approach will be adopted. As

trust diminishes, principals will rely on increasingly more intrusive oversight

efforts, from fire alarms to police patrols.

Community policing is an inherently fragile form of

oversight, insofar as it depends on collaboration between the principal and the

agent, and on rewards instead of sanctions to ensure that the agent acts as the

principal demands. But community policing also has important advantages over

police patrols and fire alarms. Notably, under community policing, principals

can get a high degree of information from the agent for relatively little

effort. Under police patrols, information usually comes at the cost of more effort,

while fire alarms trade-off minimal information for less effort. As long as it

holds together, therefore, community policing can be an attractive form of

oversight as compared with police patrols and fire alarms (Table 2).

Table 2. Forms of Oversight

|

Oversight

|

Police Patrol

|

Fire Alarm

|

Community Policing

|

|

Approach

|

Confrontational

|

Confrontational

|

Collaborative

|

|

Effort

|

High

|

Low

|

Low

|

|

Information

access

|

High

|

Low

|

High

|

|

Tools

|

Sanctions and rewards

|

Sanctions

|

Rewards

|

To illustrate how community policing works, we examine

how the Belgian and New Zealand Parliaments oversee their military and defence

officials.

In Belgium, community policing involves satisfying all

political factions that they know what the defence minister and military are

doing and why, while leaving the executive to set policy and make military

decisions. In keeping with the nature of Belgian federalism and the country's

factional political culture, the aim is to build confidence amongst Belgium's political

parties. As a result, the Belgian Parliament emphasizes sharing information in

secret committees that include representatives from these parties. The system

focuses on making all parties and factions feel that they have been properly

consulted and informed.

In New Zealand, by contrast, community policing

involves ensuring that the defence ministry and armed forces operate and make

decisions with a high degree of transparency and openness. The New Zealand

Parliament's Foreign Affairs, Defence, and Trade committee reviews and

scrutinizes estimates and military acquisitions in a public setting, using

unclassified information provided by the Ministry of Defence and New Zealand

Defence Force. This process is enabled by the New Zealand government's efforts

to increase transparency and establish a bipartisan defence consensus between

New Zealand's major parties. Underlying New Zealand's approach to community

policing is the government's belief that confidence in its ability to control

the armed forces is best achieved by showing Parliament, and by extension the

public, that the defence ministry and armed forces have nothing to hide.

Our research

suggests that community policing may be a response to past failures of

oversight. Indeed, one avenue for future

research would involve examining whether failures tend to encourage the

adoption of a community policing approach. Belgium developed new parliamentary

procedures to oversee defence procurement and military operations because of

scandals that revealed the limitations of its Parliament's oversight powers. These new procedures and the lessons of the

scandals fostered a greater effort by all sides to improve transparency. Likewise, a severe crisis in New Zealand’s

civil-military relations led to a new consensus among the major parties, the

Ministry of Defence and New Zealand’s military that produced greater

transparency and, with it, greater trust.

Our article

concludes that more work is required to see if community policing oversight

happens in larger countries and within other kinds of political structures,

such as presidential systems. Our

purpose was to establish that there is a third form of oversight that relies on

trust and collaboration, instead of suspicion and confrontation. The next step is to see if the concept has

limited or wider application.

Tuesday, January 15, 2019

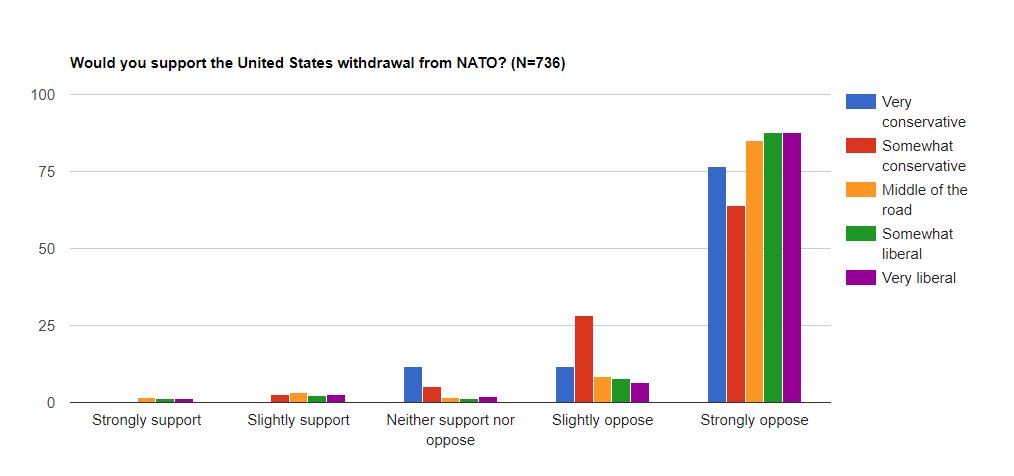

Why Does Trump Hate NATO?

Trump's desire to pull out of NATO is in the news again. Trump has very few real beliefs, but trashing NATO is perhaps just behind his racism/xenophobia and his mercantilism/corruption for most consistent beliefs/stances. Why?

First, we can consult the Trump Rules and focus on projection, numbers, and, yes, entropy.

Third, well, we could consider the Putin factor. Not so much that Putin is causing Trump to behave this way, but that Trump was an attractive candidate to the Russians both because he was a force for disorder and he was hostile to NATO. One of the basics of Russian foreign policy under Putin has been the desire to break NATO. No need to invade the Baltics to test NATO if the arsonist in the White House is trying to burn it down.

Could the US survive without NATO? Sure, its nuclear weapons mean that only terrorists will directly attack the US. But will the US thrive without it? No. Tensions, crises, and friction in Europe will come home to roost. Consider how often the US has been involved in the Mideast, which is actually at best the third most important region in the world for the US in terms of trade, investment, and all the rest. Europe remains important even as China replaces it as the second heavyweight in International Relations. NATO has been a good idea for more than 70 years because prevention is, indeed, cheaper than the cure. We have avoided a third World War, and the stability that NATO has brought to Europe is a significant part of that. IR scholars disagree a lot, but they definitely agree on NATO

As we enter an age of multipolarity where things become less certain and there is more room for misperception that can lead to war, it makes even less sense now to give up on a key source of certainty and stability. But then again, everything Trump touches turns to shit. Will the Republican Party let Trump sell off one of the most important assets of US national security? Probably.

First, we can consult the Trump Rules and focus on projection, numbers, and, yes, entropy.

- Trump has a hard time valuing reciprocity, NATO' essence via the promise of an attack upon one is an attack upon all, because he projects onto everyone else how we views things. That other countries must be ripping the US off and trying to get by via doing less precisely because that is his life-long modus operandi. He just does not get the security guarantee because he can't see anyone else keeping it since he never keeps his word. So, NATO can't mean as much to Trump as it means to damn near every major politician in the US and Europe for 7- years (De Gaulle pulled out of the operational command, but he did not pull out of NATO).

- Trump can't get any numbers right, so, of course, he does not understand that the 2% guideline--that members of NATO should contribute at least 2% of their GDP to defense--is not some kind of payment to the US for the costs of defending Europe. Nor can he understand that not everything the US spends is on European defense. Nor that 2% is a dubious measure.

- Trump does not value order. He likes chaos in his own team, fostering rivalry among his advisers. He does not value European order either, seeing the allies as competitors. It may not always be deliberate, but it is part of a basic tendency--to dismiss institutions and norms and processses. Maybe sometimes we overvalue such stuff, but avoiding major war in Europe and fostering prosperity has seemed like a pretty good deal for 70 plus years.

Third, well, we could consider the Putin factor. Not so much that Putin is causing Trump to behave this way, but that Trump was an attractive candidate to the Russians both because he was a force for disorder and he was hostile to NATO. One of the basics of Russian foreign policy under Putin has been the desire to break NATO. No need to invade the Baltics to test NATO if the arsonist in the White House is trying to burn it down.

Could the US survive without NATO? Sure, its nuclear weapons mean that only terrorists will directly attack the US. But will the US thrive without it? No. Tensions, crises, and friction in Europe will come home to roost. Consider how often the US has been involved in the Mideast, which is actually at best the third most important region in the world for the US in terms of trade, investment, and all the rest. Europe remains important even as China replaces it as the second heavyweight in International Relations. NATO has been a good idea for more than 70 years because prevention is, indeed, cheaper than the cure. We have avoided a third World War, and the stability that NATO has brought to Europe is a significant part of that. IR scholars disagree a lot, but they definitely agree on NATO

As we enter an age of multipolarity where things become less certain and there is more room for misperception that can lead to war, it makes even less sense now to give up on a key source of certainty and stability. But then again, everything Trump touches turns to shit. Will the Republican Party let Trump sell off one of the most important assets of US national security? Probably.

Friday, January 11, 2019

Move to Canada? Still More Complicated But A Bit More Realistic

The Washington Post had a piece on folks moving to Canada due to the Trump Administration, and, at first, I was like, no, not again. As someone who moved to Canada, I have long pushed back at the whole "I hate who won this election, I am moving to Canada" thing as immigration is hard. This piece had four distinct differences from ye olde silly stories:

The article mentions the cold. That can be an issue, but mostly not. As it suggests, if you get the right clothes and get your commute sorted, you will be ok. The problem is really the length of winter, not how cold it gets. Well, in Ottawa and Montreal. I have no idea how cold it gets in Edmonton, but I imagine most of these folks are moving to Calgary, Vancouver, Toronto or maybe Montreal. Of course, if they are moving to Vancouver or Toronto, they will be saving some money as they are probably a bit cheaper than Silicon Valley but not much.

The taxes are higher, but that is probably a wash when you consider the cost of health care insurance in the US. And with higher taxes come not just health care that will not bankrupt you, but maternity leave (and paternity leave in many cases) and other stuff.

Lastly, as my dissertation advisor reminds me, there is xenophobia in Canada. Quebecois politicians have competed with each other to alienate Muslims and Jews with laws about wearing religious apparel. A former Minister of Foreign Affairs is starting up a xenophobic (and transphobic) party, and the more mainstream Conservative Party is dancing with xenophobes as well. Given the diversity of Canada combined with the existing parties and electoral system, I think that xenophobia will not win. Then again, I was wrong about Trump. So, this place is not perfect by any stretch of the imagination.

Canada is a great place to live, but it is not a colder version of the US--it is a different place. And the provinces are different from each other, and there are other complexities. I am happy that Canada is smart to try to lure smart people who face potential problems due to the awful xenophobia coming out of the White House, but I am also sad that the US is losing the next generation of talent because it elected Trump. That incredibly bad decision will continue to have ramifications not just for the next couple of years but for a generation or more. The movement of smart people to Canada to avoid Trump makes clear the costs will be enduring.

- twas focused not on just dissatisfied liberals (or conservatives in 2008/12 if you can imagine that) but on immigrants to the US, so folks who didn't have deep ties and face significant risks

- due to a xenophobic regime. Trump's presidency is not ordinary, so the idea of leaving it makes more sense--escape the fascist hellscape while you can.

- that these people are valued--the programs discussed are for those with tech skills. Canada is not seeking to get any and all immigrants in the US--just those in science/tech areas. I remember back when I moved to Canada, I could have gotten five years of no Quebec taxes (a significant hunk of money) had I been a hard scientist. Social science? Nope, doesn't count.'

- there are private actors setting up firms to facilitate the transitions.

The article mentions the cold. That can be an issue, but mostly not. As it suggests, if you get the right clothes and get your commute sorted, you will be ok. The problem is really the length of winter, not how cold it gets. Well, in Ottawa and Montreal. I have no idea how cold it gets in Edmonton, but I imagine most of these folks are moving to Calgary, Vancouver, Toronto or maybe Montreal. Of course, if they are moving to Vancouver or Toronto, they will be saving some money as they are probably a bit cheaper than Silicon Valley but not much.

The taxes are higher, but that is probably a wash when you consider the cost of health care insurance in the US. And with higher taxes come not just health care that will not bankrupt you, but maternity leave (and paternity leave in many cases) and other stuff.

Lastly, as my dissertation advisor reminds me, there is xenophobia in Canada. Quebecois politicians have competed with each other to alienate Muslims and Jews with laws about wearing religious apparel. A former Minister of Foreign Affairs is starting up a xenophobic (and transphobic) party, and the more mainstream Conservative Party is dancing with xenophobes as well. Given the diversity of Canada combined with the existing parties and electoral system, I think that xenophobia will not win. Then again, I was wrong about Trump. So, this place is not perfect by any stretch of the imagination.

Canada is a great place to live, but it is not a colder version of the US--it is a different place. And the provinces are different from each other, and there are other complexities. I am happy that Canada is smart to try to lure smart people who face potential problems due to the awful xenophobia coming out of the White House, but I am also sad that the US is losing the next generation of talent because it elected Trump. That incredibly bad decision will continue to have ramifications not just for the next couple of years but for a generation or more. The movement of smart people to Canada to avoid Trump makes clear the costs will be enduring.