I had to do something this week that I would not have expected long ago. I told the editors of Ethnopolitics that I could not serve on the editorial board any longer. Why? Because I haven't done serious research on ethnic politics in quite some time. My curiosity shifted. It took a while to make that shift (the irredentism book that was the research project in the fellowship application came out in 2008). Why did I shift? At what cost? At what benefit?

I got into this career both because of a dramatic lack of imagination (I had no idea what else to do--firefighter, astronaunt, cop?) and because I am deeply curious. To a fault. The joy of the academic career is that one can pursue their curiosity as far as it can go. For me, I fell into the international relations of ethnic conflict by accident. I was thinking about sovereignty which led to secession which lead to ethnic politics. So, I asked how ethnic politics shapes the international relations of secessionist conflict.

This project bred new questions--what causes separatism, is it contagious, can institutions ameliorate ethnic conflict, and, when will countries engage in irredentism (seeking to regain supposedly lost territories... and, no, Greenland does not count). I mostly satisfied my curiosity in each area. The institutions stuff met a premature end thanks to criticism of the dataset upon which I had depended. Others entered the fray with different data and more skills, so I mostly moved on (there is still a co-authored paper in progress).

I had another ethnic conflict project--on diasporas. What causes some diasporas to be more mobilized and even more extreme than others. What happened to that project? Well, first, I learned that I really am not very good at training people to code data, so the dataset was not that productive. Second:

While I was doing the irredentism project, I spent a year in the Pentagon, which produced a big question about NATO which evolved into many questions about civil-military relations. The NATO/civ-mil stuff was so very interesting that I focused on it at the expense of the diaspora project. I can't say I have too many regrets because the NATO and civ-mil stuff has been great for me. It has led to new partnerships (including a certain big one), a really great project with a great friend from grad school that led to a, if I say so myself, cool book, a spinoff book, lots of travel to fascinating places with usually very good food.

I am now involved in the successor project--comparing the role of legislatures around the world in overseeing their armed forces. More interesting arguments, more great travel, much more excellent food. It has led to surprising findings and intellectual challenges.

The project after this one? We shall see. I have some ideas, including one with a former grad student, about bureaucratic politics and good or bad decision-making. I am pretty sure I will stick closer to the civ-mil stuff than return to the ethnic conflict stuff.

Bridging both areas has led to some fruitful exchanges and thoughts, but I am really, really far behind in what is being done these days in the IR of ethnic conflict. Which means I am a crappy reviewer for most work in this area. Hence my departure from Ethnopolitics. I am sure journals will still ask me to review that kind of stuff, but I think the only responsible position now is to say no. I can't really assess whether an argument in that area is original or making a contribution since I have lost track of the literature. I may not be that much better read in civ-mil stuff, but that is the stuff that I am teaching, reading, and writing.

There are costs. I think I could have been more productive if I stayed in the same lane. I would not have had to read new literatures--just keep up with the stuff in the one area.

But the benefit is this: I love what I am doing now. I still have ample curiosity about the stuff I am studying these days. I am sure my enthusiasm for this stuff is obvious in the classroom, which makes for better teaching. And, no, it is not about the travel, but about the conversations that make me see connections, that make me see the world a bit differently. I am not rigidly committed to my initial hypotheses, although it always does come back to institutions (thanks to UCSD).

It turns out I picked the right career. I tend to suck at things that don't interest me, and I do pretty well when I am interested. This career allows me to follow my interests. There was no grand plan except to study what I want how I want. I didn't have control over the where, but that worked out well, too. I know I am lucky.

As I finish packing for yet another APSA conference, I am looking forward to hanging out with the cool kids of civ-mil. I still hang with the ethnic conflict crowd, but a new area of research means meeting new people, and, as shy as I am (my wife is probably laughing downstairs), I do like meeting new people and learning more about the world from folks who share my enthusiasm. Hence, my effort to plan a meetup at this conference.

I hope all the APSA-goers have easy trips and less fire (see DC APSA 2014). See you soon.

International Relations, Ethnic Conflict, Civil-Military Relations, Academia, Politics in General, Selected Silliness

Pages

▼

Tuesday, August 27, 2019

Can International Organizations Be Funny?

Seth Rogen and Evan Goldberg are developing a tv show for CBS focusing on the behind the scenes people at the United Nations. The folks involved are quite funny, including the Sklar brothers (who had a great apperance on GLOW), Jay Chandrasekhar (Super Troopers and other stuff) and so on. But I can't help but wonder a couple of things:

a) is there much comedy in the daily grind at the UN?

b) if one is going to make a comedy about an international organization, is this the right one?

Sure, banging shoes on podiums was good for a laugh way back in the day during the Cold War, but I am trying to think of what might be funny among the lower ranks. Interpretation/translation errors can be a recurring theme, of course. Making fun of the latest underqualified American Ambassador might provide some comic fodder. But debates about arcane rules, failures to get consensus, talk about Article VI and VII, and such don't sing of comedic potential. Maybe my friends who study the UN can help share what would be so funny about the institution. To be sure, this has been done in movie form (thanks to Sara Mitchell for reminding me): No Man's Land. Which is kind of funny--UN peacekeeping in Yugoslavia for some laughs.

What other candidates would there be?

a) is there much comedy in the daily grind at the UN?

b) if one is going to make a comedy about an international organization, is this the right one?

Sure, banging shoes on podiums was good for a laugh way back in the day during the Cold War, but I am trying to think of what might be funny among the lower ranks. Interpretation/translation errors can be a recurring theme, of course. Making fun of the latest underqualified American Ambassador might provide some comic fodder. But debates about arcane rules, failures to get consensus, talk about Article VI and VII, and such don't sing of comedic potential. Maybe my friends who study the UN can help share what would be so funny about the institution. To be sure, this has been done in movie form (thanks to Sara Mitchell for reminding me): No Man's Land. Which is kind of funny--UN peacekeeping in Yugoslavia for some laughs.

What other candidates would there be?

- NATO? Well, War Machine was partly a NATO movie, and it was not that funny, despite my efforts to give the producer some material.

- The International Monetary Fund or the World Bank? Zzzzzzzzzzzzzzz.

- The World Health Organization has much potential: M*A*S*H meets Office Space meets ebola! It sings of comedic chaos as the WHO agents run around the world dealing with all kinds of strange diseases and varying levels of corruption and incompetent governments.

- The International Telecommunications Union? I just mention it here because it is the oldest AND I had to do research on its earliest forms when I was a first year grad student research assistant.

- The Warsaw Pact? It could be the IO equivalent of Hogan's Heroes--looking back at something fairly tragic and finding comedy in it? So easy to think of the bumbling Communists of Eastern Europe making mistakes and trying to hide them from the visiting Soviet commissars.

- International Civil Aviation Office? The usual effort to save money by producing in Canada would not diminish the realism since the ICAO is in Montreal. All kinds of hijinks can ensue between an organization which has promoted English as the language of air travel in a province that can be a bit dogmatic about French first plus having to deal with the new regulations of the post 9/11 environment could provide humor?

- The International Criminal Court? Nah, that might be good for a dramedy but not for a Seth Rogen comedy. I mean, did anyone see The Interview? Genocide is only funny twenty years later (see Hogan's Heroes) and not even then. This show's recurring theme would be "Too soon?"

- The European Union? Sure, Monty Python could probably have lots of fun with heaps of bureaucracy, and the various strange coalitions in the European parliament could provide for some sitcom fun. But how many jokes can one make about standardized toasters? Oh, but we now have that Brexit plotline that will be the gift that keeps on giving.

Monday, August 26, 2019

A Royal and Legal Experience

Today, I met a Princess, and I met Justice(s). Her Imperial Highness Princess Takamado of Japan is touring Canada to mark the 90th anniversary of Canadian-Japanese relations, and one of the events on her schedule was a lunch hosted by the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court--Richard Wagner. There were three other Justices at the event, including Hon. Madam Justice Suzanne Côté who sat my table. Or, I sat at her table.

I don't have any pictures of the event. They had a photographer, and it seemed gauche for me to take selfies so this program is the proof that it happened.

The Canadian Supreme Court staff is super-organized. The directions to a specific parking spot were clear, I was met there and then escorted. Apparently, escorts are less needed for security and more for the maze the place apparently is.

We all got there early enough to chat, with the group of SSHRC partnership grant (Queens is a partner, so she is familiar with the CDSN grant).

attendees being mostly folks with some kind of Japan connection--former ambassadors, leaders of Japan-affiliated/oriented associations, and some random academics. The food was great but, alas, it featured Canadian stuff rather than Japanese stuff. We had a variety of conversations at our table. I sat between a guy who leads a Japanese gardening association in Montreal and a Queens University official (the Princess's late husband went to Queens). So, of course, I chatted more with the Queens person who wanted to know how we prepared for the

Overall, it was a very interesting event. I didn't get to chat with Princess, but I did get to meet a bunch of interesting people and interact with a Supreme Court Justice. These are opportunities I would not get in a larger pond.

So, yeah, I am still loving Ottawa as we start our eighth year here.

I don't have any pictures of the event. They had a photographer, and it seemed gauche for me to take selfies so this program is the proof that it happened.

The Canadian Supreme Court staff is super-organized. The directions to a specific parking spot were clear, I was met there and then escorted. Apparently, escorts are less needed for security and more for the maze the place apparently is.

We all got there early enough to chat, with the group of SSHRC partnership grant (Queens is a partner, so she is familiar with the CDSN grant).

attendees being mostly folks with some kind of Japan connection--former ambassadors, leaders of Japan-affiliated/oriented associations, and some random academics. The food was great but, alas, it featured Canadian stuff rather than Japanese stuff. We had a variety of conversations at our table. I sat between a guy who leads a Japanese gardening association in Montreal and a Queens University official (the Princess's late husband went to Queens). So, of course, I chatted more with the Queens person who wanted to know how we prepared for the

Overall, it was a very interesting event. I didn't get to chat with Princess, but I did get to meet a bunch of interesting people and interact with a Supreme Court Justice. These are opportunities I would not get in a larger pond.

So, yeah, I am still loving Ottawa as we start our eighth year here.

Wednesday, August 21, 2019

Trump and The Jews: When Philo Means Anti

This piece seeks to explain Trump's Philo-Semitism--that Trump claims to be a friend of Jews but is very much not. It reminds me of my research trip to Romania in 2003 or 2004. I had never heard the term Philo-semite until it was used to refer to the leader of the Greater Romania Party. He was not able to speak with me because he was at Auschwitz proving his Philo-semitic credentials. His party was a far right, virulently xenophobic, anti-Roma party which had been anti-semitic but was changing its spots (slightly).

Why? I seem to remember it was either because he thought that the European Union cared about it and not about discriminating against Roma, so it was best to make his party more EU-friendly for the upcoming elections OR because he thought the Jews do run everything. Which is not great, really.

The WashPo piece explains that Trump and other self-proclaimed Philo-Semites believe the stereotypes about Jews but see them as good things, that they are cheap/clever (see the Horowitz list of stereotypes of advanced groups in yesterday's post), that their loyalty to Israel (not the US) makes them useful politically, etc. But the piece goes awry:

When someone proclaims themselves to be the best friends of group x, be suspicious. The best friends of Jews often are not. Trump may have given Israel a US embassy in Jerusalem and carte blanche in the occupied territories, but that makes him a friend of Netanyahu, not a friend of Jews. Trump is not a friend of Jews. The best evidence for that might just be the story of the morning (three or four shitshows ago), as he was proclaimed King of Israel by .... a Jew for Jesus. For those who don't know or don't get it, Jews for Jesus are seen by Jews as wildly anti-semitic. So, yeah, you can tell about someone's character by who their friends are. Trump's friends are no friends of Jews. So, if the Republican Jewish Committee wants to sell out its souls to suck up for a smidge of power, remember that they are betraying not Israel, but themselves.

Why? I seem to remember it was either because he thought that the European Union cared about it and not about discriminating against Roma, so it was best to make his party more EU-friendly for the upcoming elections OR because he thought the Jews do run everything. Which is not great, really.

The WashPo piece explains that Trump and other self-proclaimed Philo-Semites believe the stereotypes about Jews but see them as good things, that they are cheap/clever (see the Horowitz list of stereotypes of advanced groups in yesterday's post), that their loyalty to Israel (not the US) makes them useful politically, etc. But the piece goes awry:

"But while this form of “positive” anti-Semitism is better than the negative kind, it is still deeply dangerous"No, hells no. It is not positive and it is not better. It might even be worse because it involves betrayal. Jews see ordinary anti-semites, and they can prepare and address them and protect themselves. A Philo-Semite appears to be a friend until he/she is not, so Jews might be surprised. "Hey, Trump's daughter married a Jew and he has Jewish grandchildren, so we don't have to worry about him." Uh, yes, we do. Trump is a white supremacist, and his pals in that community don't think that Jews are whites--remember the chants at Charlottesville. Anti-semitism, misogyny, homophobia, racism, and xenophobia tend to cluster together. Trump feels more comfortable with these folks because his "philo-semitism" is just as anti-semitic as theirs.

When someone proclaims themselves to be the best friends of group x, be suspicious. The best friends of Jews often are not. Trump may have given Israel a US embassy in Jerusalem and carte blanche in the occupied territories, but that makes him a friend of Netanyahu, not a friend of Jews. Trump is not a friend of Jews. The best evidence for that might just be the story of the morning (three or four shitshows ago), as he was proclaimed King of Israel by .... a Jew for Jesus. For those who don't know or don't get it, Jews for Jesus are seen by Jews as wildly anti-semitic. So, yeah, you can tell about someone's character by who their friends are. Trump's friends are no friends of Jews. So, if the Republican Jewish Committee wants to sell out its souls to suck up for a smidge of power, remember that they are betraying not Israel, but themselves.

Tuesday, August 20, 2019

Loyalty and Modern Democracy

I am not a political theorist, and it has been decades since my last political theory class, but this is my blog, so I get to discuss whatever I want without doing extensive literature review (it is my party and I can cry if I want to).

So, excuse me if there are modern treatises that deal with this topic (see here for a great post by Peter Trumbore), but I just come to realize that this whole discussion of loyalty is very problematic. The context is that Trump has used an anti-semitic trope--that American Jews must be loyal to Israel, which, in this case, means voting Republican. There is so much wrong with this, but I want to focus on one party: loyalty.

When do we accuse someone of being disloyal in a modern democracy? When they vote for another party? Not so much. Sure in our polarized times, identity with one party (see the post earlier today) becomes so very important. But we tend not to use the language of loyalty and disloyalty.

Why do democratic citizens pay their taxes and do the other citizen stuff? Is it because they are loyal to the government? That might be the case, but we don't say it that way. We say it this way: that citizens do their share because the government is legitimate, that the institutions are seen as valid, and they led to shared expectations of what is right and wrong. I don't think Obama or Bush (either one) expected Americans to be loyal to him or to anyone else.

A poor measure, but the one I have handy, are google trends:

I have no idea if the usage of the word means anything, but this is might be the product less of Trump and more of polarization since the trend seems to start before Trump, but it jumps in the winter of 2017.

Anyhow, I can't help but think that the expectation about loyalty sounds either mob-like--don't betray the family--or authoritarian. That dictators expect unthinking obedience. So, putting aside the rank anti-semitism and hypocrisy built into Trump's statement, there is something else in it that reeks, and not in a good way. Trump really has never had any clue about what it means to be a leader in a democracy. He has never sought to represent or lead the entire American people, just his base.

So, today is just another day in Trumpland. Maybe it will end in 2021, maybe it will not. But, for now, the show goes on with the Jester-in-Chief having no clue about the substance or process involved in the job.

So, excuse me if there are modern treatises that deal with this topic (see here for a great post by Peter Trumbore), but I just come to realize that this whole discussion of loyalty is very problematic. The context is that Trump has used an anti-semitic trope--that American Jews must be loyal to Israel, which, in this case, means voting Republican. There is so much wrong with this, but I want to focus on one party: loyalty.

When do we accuse someone of being disloyal in a modern democracy? When they vote for another party? Not so much. Sure in our polarized times, identity with one party (see the post earlier today) becomes so very important. But we tend not to use the language of loyalty and disloyalty.

Why do democratic citizens pay their taxes and do the other citizen stuff? Is it because they are loyal to the government? That might be the case, but we don't say it that way. We say it this way: that citizens do their share because the government is legitimate, that the institutions are seen as valid, and they led to shared expectations of what is right and wrong. I don't think Obama or Bush (either one) expected Americans to be loyal to him or to anyone else.

A poor measure, but the one I have handy, are google trends:

I have no idea if the usage of the word means anything, but this is might be the product less of Trump and more of polarization since the trend seems to start before Trump, but it jumps in the winter of 2017.

Anyhow, I can't help but think that the expectation about loyalty sounds either mob-like--don't betray the family--or authoritarian. That dictators expect unthinking obedience. So, putting aside the rank anti-semitism and hypocrisy built into Trump's statement, there is something else in it that reeks, and not in a good way. Trump really has never had any clue about what it means to be a leader in a democracy. He has never sought to represent or lead the entire American people, just his base.

So, today is just another day in Trumpland. Maybe it will end in 2021, maybe it will not. But, for now, the show goes on with the Jester-in-Chief having no clue about the substance or process involved in the job.

Self-Esteem, Group Status, and Comparison: Understanding US Politics Today

I have blogged here before about the insights of social identity theory, and I am returning to it because it is screaming right now. How so? Let's first consider the basics.

Social identity theory (as I learned via the work of Donald Horowitz) asserts that people's sense of self, their self-esteem, rides in large part on how they feel about the group with which they identify. The logic of invidious comparison (my favorite academic phrase of all time) deduces (or induces?) that individuals will feel better about themselves if their group is doing better than other groups, and they will feel worse if their group is slighted or does worse. And this can then get quite emotional, as people get quite upset when their self-esteem is being harmed.... perceived to be harmed is the key.

The epiphany for me was the page in Horowitz's book that identified adjectives used around the world to describe "others"--groups other than one's own that either doing better or worse (advanced or backwards):

I found this persuasive for understanding ethnic conflict, but it can also be useful for explaining soccer riots. The old Jerry Seinfield routine about rooting for laundry--the uniforms of a team, regardless of who is wearing them--is on target because one identifies with "our" team.

This simple and not so simple insight (heaps of social psych I have not read on this) is very useful for understanding much around us today.

For instance, the crazy debate of the past few days has been folks who are upset about the NYT 1619 series--which marks the 400 anniversary of the start of slavery in North America with a bunch of pieces that elaborate on how much of today's politics, economics, and even traffic jams are the product of the past, particularly of slavery in the US. Some folks are very, very upset. Putting aside the ridiculousness of Newt Gingrich supposedly being upset by this (with the best twitter response of this or any era), some people are upset because they see it as a critique of white Americans. By being critical of the founders of the US, by showing that racism is hard-wired into so many facets of American politics, society, and economics, the 1619 series is seen by members of a particular group as diminishing the value of that group and thus the self-esteem of its members. If much of the success of white Americans relative to other groups is due to unfair advantages, and that is what slavery and its legacy has produced, then the members of that group will feel their self-esteem diminish. They must attack those efforts that might make their group look bad.

Yes, I am a white guy writing about this, but not all (sorry) white Americans share the same sense of their identity. My identity and my self-esteem, like many other folks, does not ride or die on the sense of the United States as a white country. Indeed, my self-esteem takes a hit when the US as a multiethnic country is attacked or undermined. The key is this: while others have some say in one's own identity (Nazis don't think I am white), the groups with whom one identifies is actually somewhat within the control of individuals. This is how people can leave white supremacist organizations--they start to identify less with white people and more with some other group. One does not have to be a Mets fan all of one's life (damn it), but it can be hard to see the world differently and identify differently.

Things get complex because people have multiple identities (this is where intersectionality comes in), and often one identity has more salience than others. One of the events of the past week that truly annoyed me from an outside perspective was to see the Log Cabin Republicans re-endorse Donald Trump. This group consists of gay Republicans, and it is abundantly clear that Trump has been awful to the LGBTQ community. These individuals, well, most of them, find it more important to identify as Republican than as LBGTQ apparently.

Similarly, in the election of 2016, we saw many non-Muslim Indian Americans line up in favor of Trump because they shared a common animus--Muslims. It is not so much that the group had the same identity as Trump, but both they and Trump felt better as Muslims in the US were marginalized. Some Indian Americans may be re-thinking that now as it turns out that white supremacists hate not just Muslims but Indians.

The larger point here is that we are seeing various people lash out against criticisms of their group because they feel their own status, their own sense of self, is diminished.

How to combat the dynamics of social identity? Cross-cutting cleavages used to be a favorite--that it is ok to have different identities as long as people are not always divided into the same groups. That is, it is better if class, race, and party are not always dividing a place into the same sub-groups. Political polarization is so dangerous precisely because everyone now is either in group a or group b. Having racially, religiously, linguistically diverse parties reduces the tensions because not every political decision implicates one's identity. The Republicans as a largely white, predominantly evangelical party are more likely to have to suffer from the identity dynamics because the fortunes of the party are connected to these groups' sense of self. The failure of Democrats to win an office (hmm, the Mets seem to come to mind again) may or may not have a big emotional impact as the identities of its members are not so lined up with the party. It might suck to lose, but it does not feel as much of an insult to the identities of atheists or non-orthodox Jews or LGBTQ or other members of this plural coalition because it is not so much about any individual group. For the Republicans lately, any defeat is a defeat for whites and for evangelicals. Which is why this is so much more of a blood sport for one party than another.

It is usually seen that the multiethnic party is at a disadvantage compared to the monoethnic party in the game of outbidding--that the monoparty can peel off voters of the same identity from the multiethnic party. These days, those voters are called white working class in the US. But perhaps the multiethnic party is better off in this competition for not being so easily captured and tied to a random outbidder precisely because they simply don't have as much invested in the party's well-being. That is, to say it as ruthlessly as I can, the GOP is now a bunch of cultists tied to Trump. The Democrats are too diverse to be quite as chained to any leader and especially one as awful as Trump.

This might make it hard to win elections, but it makes me feel good. See, I am subject to social identity dynamics.

Social identity theory (as I learned via the work of Donald Horowitz) asserts that people's sense of self, their self-esteem, rides in large part on how they feel about the group with which they identify. The logic of invidious comparison (my favorite academic phrase of all time) deduces (or induces?) that individuals will feel better about themselves if their group is doing better than other groups, and they will feel worse if their group is slighted or does worse. And this can then get quite emotional, as people get quite upset when their self-esteem is being harmed.... perceived to be harmed is the key.

The epiphany for me was the page in Horowitz's book that identified adjectives used around the world to describe "others"--groups other than one's own that either doing better or worse (advanced or backwards):

I found this persuasive for understanding ethnic conflict, but it can also be useful for explaining soccer riots. The old Jerry Seinfield routine about rooting for laundry--the uniforms of a team, regardless of who is wearing them--is on target because one identifies with "our" team.

This simple and not so simple insight (heaps of social psych I have not read on this) is very useful for understanding much around us today.

For instance, the crazy debate of the past few days has been folks who are upset about the NYT 1619 series--which marks the 400 anniversary of the start of slavery in North America with a bunch of pieces that elaborate on how much of today's politics, economics, and even traffic jams are the product of the past, particularly of slavery in the US. Some folks are very, very upset. Putting aside the ridiculousness of Newt Gingrich supposedly being upset by this (with the best twitter response of this or any era), some people are upset because they see it as a critique of white Americans. By being critical of the founders of the US, by showing that racism is hard-wired into so many facets of American politics, society, and economics, the 1619 series is seen by members of a particular group as diminishing the value of that group and thus the self-esteem of its members. If much of the success of white Americans relative to other groups is due to unfair advantages, and that is what slavery and its legacy has produced, then the members of that group will feel their self-esteem diminish. They must attack those efforts that might make their group look bad.

Yes, I am a white guy writing about this, but not all (sorry) white Americans share the same sense of their identity. My identity and my self-esteem, like many other folks, does not ride or die on the sense of the United States as a white country. Indeed, my self-esteem takes a hit when the US as a multiethnic country is attacked or undermined. The key is this: while others have some say in one's own identity (Nazis don't think I am white), the groups with whom one identifies is actually somewhat within the control of individuals. This is how people can leave white supremacist organizations--they start to identify less with white people and more with some other group. One does not have to be a Mets fan all of one's life (damn it), but it can be hard to see the world differently and identify differently.

Things get complex because people have multiple identities (this is where intersectionality comes in), and often one identity has more salience than others. One of the events of the past week that truly annoyed me from an outside perspective was to see the Log Cabin Republicans re-endorse Donald Trump. This group consists of gay Republicans, and it is abundantly clear that Trump has been awful to the LGBTQ community. These individuals, well, most of them, find it more important to identify as Republican than as LBGTQ apparently.

Similarly, in the election of 2016, we saw many non-Muslim Indian Americans line up in favor of Trump because they shared a common animus--Muslims. It is not so much that the group had the same identity as Trump, but both they and Trump felt better as Muslims in the US were marginalized. Some Indian Americans may be re-thinking that now as it turns out that white supremacists hate not just Muslims but Indians.

The larger point here is that we are seeing various people lash out against criticisms of their group because they feel their own status, their own sense of self, is diminished.

How to combat the dynamics of social identity? Cross-cutting cleavages used to be a favorite--that it is ok to have different identities as long as people are not always divided into the same groups. That is, it is better if class, race, and party are not always dividing a place into the same sub-groups. Political polarization is so dangerous precisely because everyone now is either in group a or group b. Having racially, religiously, linguistically diverse parties reduces the tensions because not every political decision implicates one's identity. The Republicans as a largely white, predominantly evangelical party are more likely to have to suffer from the identity dynamics because the fortunes of the party are connected to these groups' sense of self. The failure of Democrats to win an office (hmm, the Mets seem to come to mind again) may or may not have a big emotional impact as the identities of its members are not so lined up with the party. It might suck to lose, but it does not feel as much of an insult to the identities of atheists or non-orthodox Jews or LGBTQ or other members of this plural coalition because it is not so much about any individual group. For the Republicans lately, any defeat is a defeat for whites and for evangelicals. Which is why this is so much more of a blood sport for one party than another.

It is usually seen that the multiethnic party is at a disadvantage compared to the monoethnic party in the game of outbidding--that the monoparty can peel off voters of the same identity from the multiethnic party. These days, those voters are called white working class in the US. But perhaps the multiethnic party is better off in this competition for not being so easily captured and tied to a random outbidder precisely because they simply don't have as much invested in the party's well-being. That is, to say it as ruthlessly as I can, the GOP is now a bunch of cultists tied to Trump. The Democrats are too diverse to be quite as chained to any leader and especially one as awful as Trump.

This might make it hard to win elections, but it makes me feel good. See, I am subject to social identity dynamics.

Saturday, August 17, 2019

Civil-Military Relations After Afghanistan

Jim Golby and Peter Feaver have a super-interesting piece at the Atlantic on what a deal with the Taliban might mean for US civil-military relations. They were smart enough to ask questions in an experimental fashion this summer about attitudes about a potential end to the Afghanistan war--victory or defeat. The timing is fantastic, as the US is currently working on a deal with the Taliban. That deal may be quite problematic--a post for another day--so their survey is really quite prescient by asking different people similar questions but with additional info about a potential victory or defeat in Afghanistan. For application to the current situation, one can imagine the deal going in either direction, selling out the Afghans to the Taliban in exchange for the US getting out or getting a peace deal with the Taliban share power with the Afghans we have supported and denying the place as a base for terrorism.

The basic findings are straightforward

Of course, I had to raise a question about one key aspect: that 75% of civilians and 90% of the veterans expressed confidence in the military, sans experiment--is this too high? In most democracies these days, the citizens have more confidence in the armed forces than other institutions, and this makes some sense. Unlike most other institutions, such as the legislature, the executive, the courts increasingly, the media, the armed forces are not seen as partisan. That is a good thing. But the whole "support our troops" mantra may cause folks to be less critical of the armed forces than they should be.

While much of the blame for the forever wars rightfully should go to the civilians that put the militaries into difficult spots, the various armed forces have not always performed brilliantly. We saw the US military subvert the intent of the President who wanted population-centric war while the Marines went to Helmand instead. We saw a German colonel order an airstrike despite not having eyes on the ground, which led to more than a hundred Afghan civilians getting killed. Not one, but two prison breaks took place while the Canadians were in Kandahar. I can go on, but the major point is this: the armed forces of the US and its allies have had mixed success in the forever wars. Maybe we should not be quite as confidence in their competence? Or at least, maybe we should be asking questions, even if the answers ultimately lead to a clearer understanding of how outstanding they were.

PS I have a quibble--they state that Obama didn't talk about Afghanistan. They cite a previous Feaver piece to support that, but that piece has no numbers to show Obama talked more or less about Afghanistan than Bush did, especially Bush after 2005. I did count Harper talking about Afghanistan over time, which showed some interesting patterns in Adapting in the Dust.

The basic findings are straightforward

- Americans doesn't see the Afghanistan war as a mistake (unlike the Iraq war)

- They want it to end. Tis a forever war, and Americans don't like that.

- Support for withdrawal among civilians is pretty consistent, but among veterans, it matters whether the troops are coming home in victory or defeat, with support for withdrawal declining if it is in defeat.

- veterans tended to give civilian leaders credit for a victory

- nonveteran civilians tended to give military leaders credit for a victory

- veterans tended to blame civilian leaders for a defeat

- nonveteran civilians tended to blame military leaders for a defeat.

Of course, I had to raise a question about one key aspect: that 75% of civilians and 90% of the veterans expressed confidence in the military, sans experiment--is this too high? In most democracies these days, the citizens have more confidence in the armed forces than other institutions, and this makes some sense. Unlike most other institutions, such as the legislature, the executive, the courts increasingly, the media, the armed forces are not seen as partisan. That is a good thing. But the whole "support our troops" mantra may cause folks to be less critical of the armed forces than they should be.

While much of the blame for the forever wars rightfully should go to the civilians that put the militaries into difficult spots, the various armed forces have not always performed brilliantly. We saw the US military subvert the intent of the President who wanted population-centric war while the Marines went to Helmand instead. We saw a German colonel order an airstrike despite not having eyes on the ground, which led to more than a hundred Afghan civilians getting killed. Not one, but two prison breaks took place while the Canadians were in Kandahar. I can go on, but the major point is this: the armed forces of the US and its allies have had mixed success in the forever wars. Maybe we should not be quite as confidence in their competence? Or at least, maybe we should be asking questions, even if the answers ultimately lead to a clearer understanding of how outstanding they were.

PS I have a quibble--they state that Obama didn't talk about Afghanistan. They cite a previous Feaver piece to support that, but that piece has no numbers to show Obama talked more or less about Afghanistan than Bush did, especially Bush after 2005. I did count Harper talking about Afghanistan over time, which showed some interesting patterns in Adapting in the Dust.

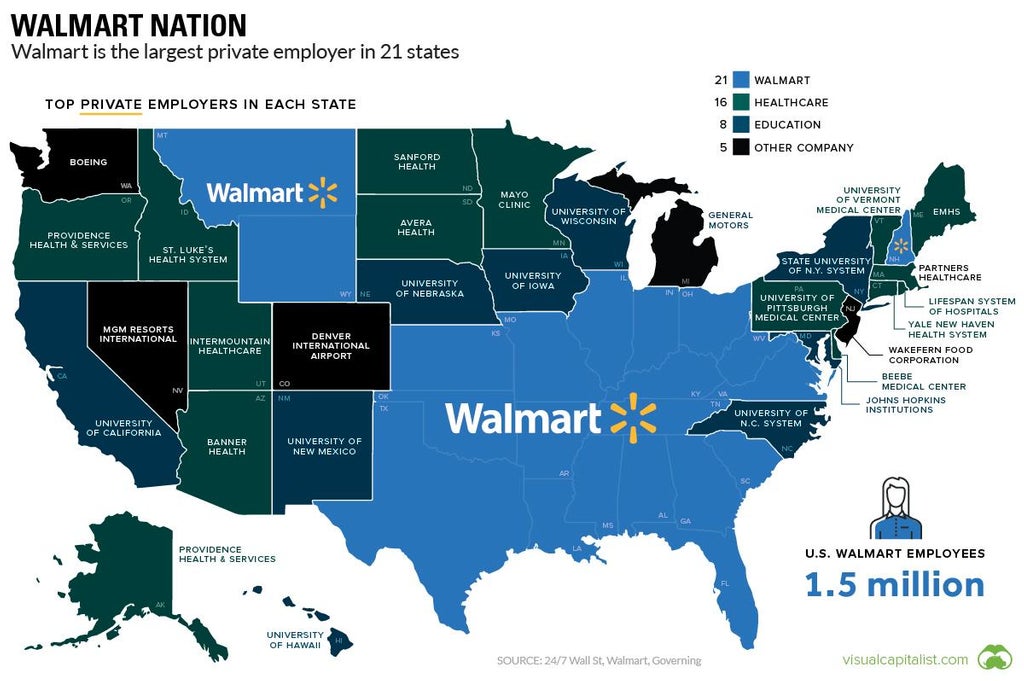

Map Quiz! Biggest Private Employer in Each State

Ok, this is not a quiz but a series of reactions to this pic:

A few obvious patterns here. Of course, the Walmart of it all. What does it say that Walmart is the biggest employer for 21 states? That they have done a great job of wiping out the competition, I guess. Mostly red states plus Illinois and Virginia. Hmm. Lots of correlation/causation possibilities here.

Let's come back to this, but focus on the other trends:

To be sure, this map is deceptive since it is of largest employers and does not tell us about percentage compared to the rest of the state's population. It may be that Walmart employees are actually not that big of a voting block in many of these states (Texas?). Indeed, only 1.5 million employees--a lot for one business, but not that big of an electoral constituency.

Just something to think about on a Saturday morning rather than reading graduate student work or reviewing a journal article.

A few obvious patterns here. Of course, the Walmart of it all. What does it say that Walmart is the biggest employer for 21 states? That they have done a great job of wiping out the competition, I guess. Mostly red states plus Illinois and Virginia. Hmm. Lots of correlation/causation possibilities here.

Let's come back to this, but focus on the other trends:

- State university systems (which are not private employees, but whatevs). California (woot for my PhD alma mater), New Mexico, Maryland, Nebraska, Iowa, Wisconsin, North Carolina, Hawaii! A mix politically, but, damn, given that universities not only educate the next generation but are incubators of innovation and economic growth, this would seem to be a good thing.

- Health care systems--Oregon, Idaho, Utah, Arizona, Dakotas North and South, Minnesota, Vermont, Maine, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Connecticut, Massachusetts. Hmm. Is centralization/monopolization of health care a good thing? In private hands, bad. Public hands? Good. Damn, the US health care system sucks mightily. I mean, it might make sense that such a service oriented business might employ a great number of people--everyone gets sick, everyone dies, etc. But I wonder what this figure would look like for places with public health care--would health care still be a top employer? Perhaps even more so since one can imagine California's health care providers together would employ more than the UC system (of course, if we combined UC with Cal State Universities...)

- Three outliers in order of increased funkiness: GM in Michigan--not a surprise but we wonder how long this will last; Wakefern Food Corp in New Jersey--that the food business is that concentrated and that big (or that the other potential big employing industries have multiple firms?); and finally and most strange--Denver International Airport. WTF? I mean, I know one of its lawyers, but perhaps this says more about how the rest of Colorado's employees are split up into different entities? That maybe there are multiple health care systems? I do know there are multiple university systems.

- the status quo, where the company store helps to manipulate the system so that people vote against their economic interests

- a unionized populace (see, Phil, I like unions sometimes) that takes all of their political power and advocates for better working conditions, national health care, etc.

To be sure, this map is deceptive since it is of largest employers and does not tell us about percentage compared to the rest of the state's population. It may be that Walmart employees are actually not that big of a voting block in many of these states (Texas?). Indeed, only 1.5 million employees--a lot for one business, but not that big of an electoral constituency.

Just something to think about on a Saturday morning rather than reading graduate student work or reviewing a journal article.

Wednesday, August 14, 2019

Holy Hierarchy, Batman! Dissertation Defences and Food?

A few weeks ago, this thing became a topic on twitter and it just got new energy:

When I first heard of this, I was flummoxed. Grad students are, pretty much by definition, poor. Asking them to pay for the food and drinks at their dissertation defenses (I hate using the word thesis for the big hunk of research written by a PhD student) is just awful. The inequality here is stark, as the grad student has both little money and little power. The tenured profs (if you choose untenured profs to be your supervisor, well, damn) have both money and power, at least more than the grad student.

So, adding financial pressure to an already potentially fraught relationship is just ridiculous. And wildly inappropriate. I have never seen this "custom" where I was trained or where I have worked (three Phd granting institutions). This may vary by discipline and/or by institution, but it is simply unfair and abusive.

This week, thanks to my trip to Normandy earlier this summer, I have been re-watching Band of Brothers. In a scene taking place just before the big jump into Normandy, the beloved Lt. Winters is seen castigating the soon to be beloved Lt. Buck Compton. For what? For gambling with his men. Buck thinks this is a great way to learn the new guys, since he just got assigned to Easy Company. Winters argues that he should never put his men in the position where they are giving stuff, that they are in debt to, a superior officer.

While academia is not usually seen as hierarchical as the military (I have been disobedient to more than one department chair in my time--with mostly modest consequences), the relationship between adviser and advisee is not that dissimilar from officer to enlisted, as there is a wide gap in between in terms of money and power in both relationships. I don't hold the lives of my students in my hands, unlike a military officer, but I do hold their careers in my hands. I may not think about that much, but I am pretty sure the students do. That is what privilege is all about--those who have it tend not to think about it, those who don't tend to feel threatened or insecure.

Which goes to something very basic, identified by a dear departed uncle: with great power comes great responsibility. While academics may not think they have great power, they very much do so over the PhD students they supervise. I try to pay the bill whenever I have coffee or beer or lunch or dinner with graduate students (sometimes I forget or they move quickly). I damn well never expect them to pay for me.

So, I hope my fellow academics in other disciplines/regions start to consider exactly what they are doing with this tradition and end it.

I fear this means the end of my caviar and champagne brunches. https://t.co/2NaFxv1HKv— Daniel W. Drezner (@dandrezner) August 14, 2019

When I first heard of this, I was flummoxed. Grad students are, pretty much by definition, poor. Asking them to pay for the food and drinks at their dissertation defenses (I hate using the word thesis for the big hunk of research written by a PhD student) is just awful. The inequality here is stark, as the grad student has both little money and little power. The tenured profs (if you choose untenured profs to be your supervisor, well, damn) have both money and power, at least more than the grad student.

So, adding financial pressure to an already potentially fraught relationship is just ridiculous. And wildly inappropriate. I have never seen this "custom" where I was trained or where I have worked (three Phd granting institutions). This may vary by discipline and/or by institution, but it is simply unfair and abusive.

This week, thanks to my trip to Normandy earlier this summer, I have been re-watching Band of Brothers. In a scene taking place just before the big jump into Normandy, the beloved Lt. Winters is seen castigating the soon to be beloved Lt. Buck Compton. For what? For gambling with his men. Buck thinks this is a great way to learn the new guys, since he just got assigned to Easy Company. Winters argues that he should never put his men in the position where they are giving stuff, that they are in debt to, a superior officer.

While academia is not usually seen as hierarchical as the military (I have been disobedient to more than one department chair in my time--with mostly modest consequences), the relationship between adviser and advisee is not that dissimilar from officer to enlisted, as there is a wide gap in between in terms of money and power in both relationships. I don't hold the lives of my students in my hands, unlike a military officer, but I do hold their careers in my hands. I may not think about that much, but I am pretty sure the students do. That is what privilege is all about--those who have it tend not to think about it, those who don't tend to feel threatened or insecure.

Which goes to something very basic, identified by a dear departed uncle: with great power comes great responsibility. While academics may not think they have great power, they very much do so over the PhD students they supervise. I try to pay the bill whenever I have coffee or beer or lunch or dinner with graduate students (sometimes I forget or they move quickly). I damn well never expect them to pay for me.

So, I hope my fellow academics in other disciplines/regions start to consider exactly what they are doing with this tradition and end it.

A Semi-Spew Contest: A Correct Number?

I have long argued that anytime Trump uses a number, it is wrong. It is one of the basic rules for understanding Trump.

So, I tweeted thusly in reaction to yet another Daniel Dale story about Trump and his wildly inaccurate statements:

I didn't get any serious answers, which is somewhat telling. Instead, I got these answers:

[I used pics of the tweets rather than embedding all of them because I have limited time--one of the reasons I post less often these days]

The contest is still open: let me know of a time where Trump uses a number accurately. Or give me more unserious answers, because we can use all of the amusement we can in these dark times.

So, I tweeted thusly in reaction to yet another Daniel Dale story about Trump and his wildly inaccurate statements:

I am starting to think of a contest: can someone name a situation where Trump got a number correct?— Steve Saideman (@smsaideman) August 13, 2019

I didn't get any serious answers, which is somewhat telling. Instead, I got these answers:

[I used pics of the tweets rather than embedding all of them because I have limited time--one of the reasons I post less often these days]

The contest is still open: let me know of a time where Trump uses a number accurately. Or give me more unserious answers, because we can use all of the amusement we can in these dark times.