After news of Canadian Armed Forces moving to the Atlantic provinces to help with the post-Hurricane Fiona, I tweeted that we need to think about CAF priorities thusly:

I keep harping on this, but since Canada will never have a real FEMA, CAF needs to get used to domestic emergency ops as its day job, not just an inconvenience that gets in the way of training. Rather than 4th of 4 priorities, it really needs to accept this as tied for 1st https://t.co/tD8K1C7avg

— Steve Saideman (@smsaideman) September 24, 2022

It is not a new thing for me to say, but it seemed to get a lot more play than usual. Some active/retired CAF people took it most personally, so I thought I would explain what I meant and then discuss the (over)reaction.

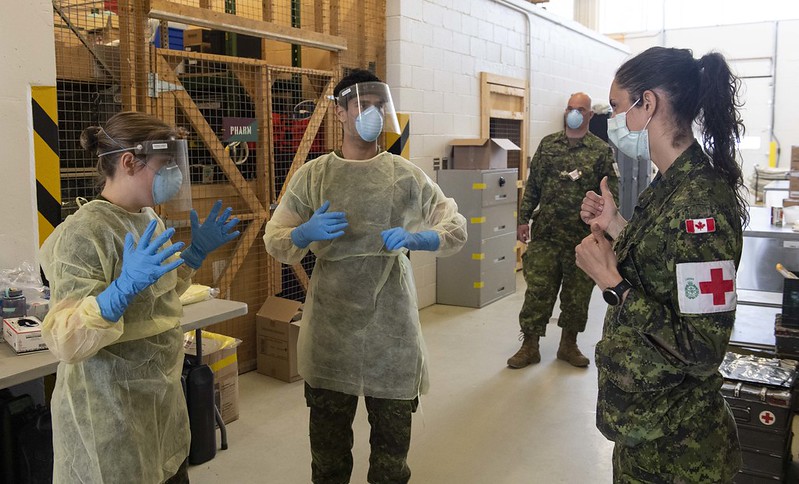

In every defense review, domestic emergency operations, known as aid to civil power, is listed as one of the four major priorities (defence of Canada, defence of North America, NATO--if I recall correctly--are the other three), but is always fourth. And it is fourth when it comes to spending, training, promotion, procurement, etc. In public and private discussions, senior CAF officers tend to refer to domestic emergency operations as an inconvenience--something that disrupts training cycles and deployment schedules. However, as the pandemic made abundantly clear,

In every defense review, domestic emergency operations, known as aid to civil power, is listed as one of the four major priorities (defence of Canada, defence of North America, NATO--if I recall correctly--are the other three), but is always fourth. And it is fourth when it comes to spending, training, promotion, procurement, etc. In public and private discussions, senior CAF officers tend to refer to domestic emergency operations as an inconvenience--something that disrupts training cycles and deployment schedules. However, as the pandemic made abundantly clear,

Canadians face far greater threats from viruses and weather than from distant authoritarian regimes. Oh, and if those regimes wanted to get super serious and throw nukes around, there is nothing that the CAF could do to stop it (and nothing the US could do either--ABM tech is still not proven/reliable/nor ever able to knock down every missile sent our way).

The pace of these nature-induced domestic operations has been increasing due to climate change, something that the current Chief of Defence Staff Wayne Eyre noted when he was army chief way back in 2020 before the pandemic struck North America:"“If this becomes of a larger scale, more frequent basis, it will start to affect our readiness.” Note the sense here that the domestic ops are getting in the way of the day job.

In my conversations with CAF folks, I have heard that promotion and leave calculations reward folks who go on operations abroad but not so much for operations at home. This helps to foster a mindset and a focus.

The question I was raising essentially is not whether the CAF is trained to do ops at home, but whether they spend enough time, money, procurement, effort, etc to do the stuff at home really well. Or is it a matter of short training for each potential emergency and showing up when asked? I really don't know how much more training/spending/etc is required, but I do think we/they need to have a real conversation about how priority #4 is perhaps approaching priority #1.

The pushback I got was from folks saying that if we spent more time training for domestic ops, that leaves us less well trained to fight at the highest, most intense levels AND that training for that stuff puts us in good shape for the domestic stuff. I honestly don't know how transferable the skills are from combat to dealing with floods/fires/ice storms/pandemics/etc. I think this is all worth exploring.

I also wonder how much effort has been done to learn from past operations. It seems to me that most of this stuff happens at lower levels, so that there is not much lesson learning across the country. A lot of this involves relationships with provinces and municipalities, and I can't help but wonder if there is variation in all of this stuff. Alas, defence scholars haven't spent much time studying this stuff. Our latest big grant at the CDSN has this as one focal point, so perhaps my tweet was about establishing ourselves on this corner and justifying it.

Tis worth noting that some folks seemed super-insulted by the tweet, that suggesting that the military work harder on non-kinetic (not combat stuff) is not only a huge mistake but an insult to the troops. Not sure why that is, unless one's identity is entirely bound up with the combat stuff. So, I can't help but think that the discussion of culture change, which has focused mostly on sexual misconduct, somewhat on better inclusion and equity of historically excluded groups, a bit on abuse of power, might also consider other elements of the CAF culture. Valorizing combat at the expense of helping Canadians at home? That seems a bit problematic to me. But then again, I am an ivory tower know-nothing prof.

To be clear, I would much rather have a civilian agency equivalent to the American Federal Emergency Management Agency doing this stuff, but I doubt that will happen. It would require the provinces and the federal government to get along well enough to solve the cost-sharing, moral hazard problems that are rife here. Given that the provinces are still asking for more health $ from the feds as they cut taxes and spend previous allotments of health care money on anything but the pandemic, I am skeptical about the prospects of a real Canadian FEMA.

And, yeah, not so long ago, I scoffed at the idea of military folks spending heaps of time on domestic emergencies. When I first moved here and started doing research on the CAF and Afghanistan, I was stunned to see officers have the ice storm of 1998 as one of the most significant operations. But after watching Vancouver isolated by floods perhaps more effectively than a Russian or Chinese attack could, the pandemic leading to soldiers in elder care facilities (another provincial failure), and on and on, I am realizing that we have to at least ask if we have our priorities right. If folks fear those questions, then those questions need to be asked more loudly.