|

| The conference was in Alex Trebek Hall! |

The theme of the conference was "Disorder, Disruptions, and Directions" and a fourth D was implicit in the title and not so implicit in many of the talks: Depressing. Why? Trump, Brexit, populism, the apparent decline of the Liberal International Order. I was assigned the topic of Trump (I wonder why, I rarely think or write about him). The other speakers were from Canada, the US, and Europe. Because we had a bunch of government types, we had to follow Chatham House Rule, which means we can talk about what was said but not attribute to anyone. I am not a fan, but I mostly behaved. I then asked a couple of the speakers if I could cite them, and since they are academics, they said hells yeah.... or something like that.

William Wohlforth of Dartmouth gave the keynote, and focused on US Grand Strategy After Trump. It was actually US Grand Strategy before and after Trump. As a reasonable Realist who has written on such stuff, Wohlforth raised a basic question--what is the reference point one has to "the good times." I was reminded of my own piece, currently in process that asks a meta version of that question--when was peak Grand Theory. Anyhow, his basic point is that the US had overextended before Trump--either under Clinton or under Bush, and so the US under Obama and now Trump has to deal with the realities of commitments and efforts being beyond the capabilities of the US.

William Wohlforth of Dartmouth gave the keynote, and focused on US Grand Strategy After Trump. It was actually US Grand Strategy before and after Trump. As a reasonable Realist who has written on such stuff, Wohlforth raised a basic question--what is the reference point one has to "the good times." I was reminded of my own piece, currently in process that asks a meta version of that question--when was peak Grand Theory. Anyhow, his basic point is that the US had overextended before Trump--either under Clinton or under Bush, and so the US under Obama and now Trump has to deal with the realities of commitments and efforts being beyond the capabilities of the US.He argued that the US had three tasks--to manage the global environment to keep threats away; to manage the economic order, and to foster an institutional order. Doing more than that--democracy promotion, fighting terrorism everywhere, regime changing Iraq--is not sustainable. With the end of the Soviet Union, the primacy of the US, Wohlforth argues, allowed the US to become a revisionist state--trying to change other states and the world as the US became less tolerant of risk. One of the basic problems is that folks treated the international liberal order as a bicycle--if it is not always moving forward it falls over.

So where are we now? Wohlforth asked us to focus on what Trump has been doing, rather than what he tweets (alas, any effort to suggest Trump is not too bad is usually undone within hours by Trump behavior). The power balance shift is significant but exaggerated. There is still only one superpower. The interests of US engagement, when not overextended, are still greater than the costs. The institutional stuff is actually pretty robust. So expect a less revisionist, more status quo President after Trump.

Overall, I found the talk super engaging, and it make me think about my priors. Definitely shared points of agreement, as I have long argued that Obama was not retrenching, but just less willing to risk money and blood for dubious gains. I am not so sure that Bosnia or Kosovo were really over-extension. While the folks in the Pentagon thought they were expensive efforts that challenged readiness, they were nothing in comparison to dual wars in Afghanistan and Iraq plus all of the lesser conflicts. I think the real over-extension was not Kosovo or modest democracy promotion but Iraq--that was incredibly expensive, demonstrated American ineptness, and created so many problems that continue to cause the US to expend much effort (Syria, Iraq).

The key for Realists and for pragmatic folks like myself (I am realistic about stuff, but I think that anarchy is not so determining and that interests come from domestic politics more than from the international system) is that grand strategy is about balancing capabilities and commitments. The US, by getting stuck in Iraq, skewed commitments, and by the domestic political effort to condemn taxes as evil, have undermined American capabilities. The gutting of governance, I think, besides racism, is the real cause of rising populism. Yes, international trade and automation cause shocks and disruption (damn, I hate that word), but governments failed to react because key actors in domestic politics thought austerity was the way out. Which meant people paid the price, not corporations.

Anyhow, a great talk and now I feel that I read Wohlforth's book without actually reading it. Woot!

The other talk I'd like to highlight is Andrea Lane's. Andrea is a graduate student at Dalhousie, but I think most people think she is a junior prof. She definitely held her own in a crowd of graybeards like myself. She was tasked to consider what a feminist defence policy would look like, and she started by invoking my favorite movie for any presentation:

The other talk I'd like to highlight is Andrea Lane's. Andrea is a graduate student at Dalhousie, but I think most people think she is a junior prof. She definitely held her own in a crowd of graybeards like myself. She was tasked to consider what a feminist defence policy would look like, and she started by invoking my favorite movie for any presentation: Lane was right was that Liberals are doing very little:

- eliminating sexual harassment and assault is "a bare minimum."

- there is more to the problems of CAF recruitment and retention--systemic stuff.

- training others to do better gender stuff while peacekeeping rings hollow if Canada isn't doing peacekeeping.

- Less defence $ as they go mostly to men, helping men "all the way down", whereas "butter" or social programs tend to help women more. Fun pic of shipbuilding stuff featuring men, men and men.

- Smaller defence industry as these largely male jobs are much better paid/pensioned & tax subsidized while women's jobs are none of things.

- Defence exports go to places where women and children are killed (Saudis make the LAV look mighty bad)

- Radically revise recruiting--stop recruiting men until we reach 50% women?

- A subpoint on this slide was more realistic and one I would really like: stop the steady increase in use and valorization of SOF. Male only SOF being used means women don't get combat experience which stunts their career development. And for me, this is bad because SOF have less oversight and are ways for politicians to use the military without being as accountable.

- Reduce domestic abuse in military families. This was in her radical proposals but should be in her "the least one can do" section.

- Her less radical proposal--focus on girls/women when building the cyber force. Make that a woman's job--good pay, flexibility, etc. The super important point: "without concerted effort to create woman-friendly cyber program, it will be male-dominated."

Overall, a great day--they brought in very interesting people, kept things moving, and had us all drinking from the firehouse of insight. CIPS did a great job of celebrating their 10th anniversary. I definitely will try to steal their recipe for successful conferences in case one of my network grant applications succeeds.

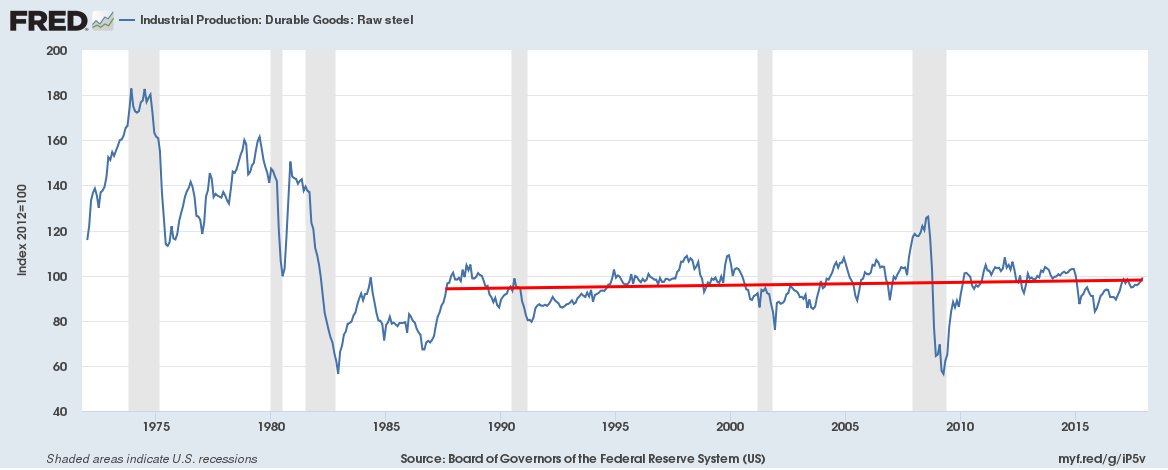

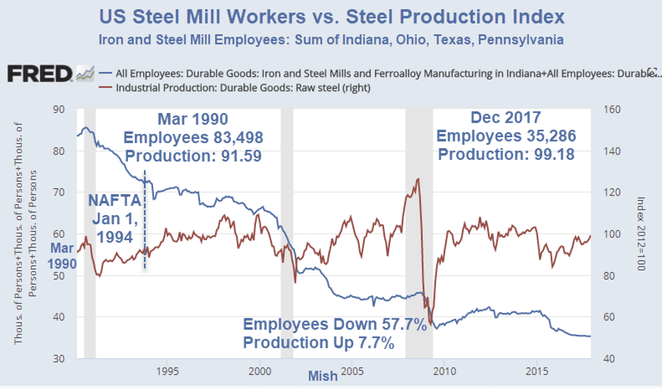

Well, steady in terms of output but not steady in terms of employment. Another good tweet last night indicated that the productivity gain for making steel means that 2 people can make as much steel now as 10 could in 1980. So, the problem is not Canada, nor is it Germany or Japan or China, but increased productivity (yes, IPE is more complicated than that so I am simplifying).

Well, steady in terms of output but not steady in terms of employment. Another good tweet last night indicated that the productivity gain for making steel means that 2 people can make as much steel now as 10 could in 1980. So, the problem is not Canada, nor is it Germany or Japan or China, but increased productivity (yes, IPE is more complicated than that so I am simplifying).