When Trump talks about trade deficits and blasts Japan and Germany, he seem to be invoking a time where those two countries seemed to be the biggest threats to American producers. Japan's economy has been stagnant for more than two decades. Both countries have firms that have invested significantly in US-based production. So, these views have mostly been overcome by events that Trump has not apparently noticed.

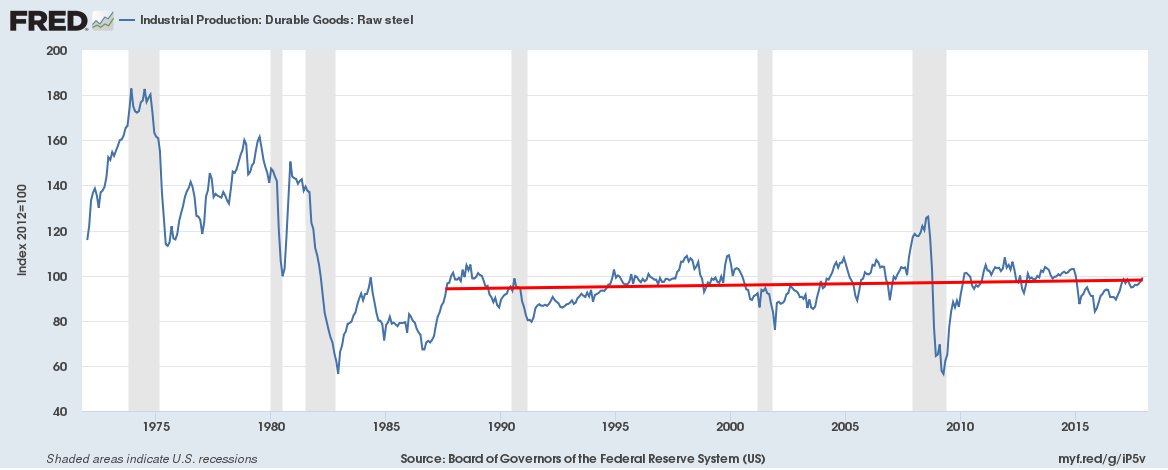

Trump's views on steel and aluminum, that these industries are on steep decline, makes sense if you compare the mid 1980s with the previous decades:

but these industries have been mostly pretty steady since then (big dip during the financial crisis, and mostly profitable as of late, and see here for more figures, h/t to Scott Lincicome).

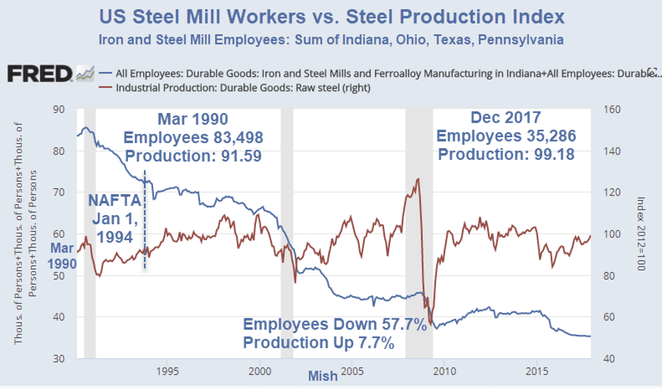

Well, steady in terms of output but not steady in terms of employment. Another good tweet last night indicated that the productivity gain for making steel means that 2 people can make as much steel now as 10 could in 1980. So, the problem is not Canada, nor is it Germany or Japan or China, but increased productivity (yes, IPE is more complicated than that so I am simplifying).

Well, steady in terms of output but not steady in terms of employment. Another good tweet last night indicated that the productivity gain for making steel means that 2 people can make as much steel now as 10 could in 1980. So, the problem is not Canada, nor is it Germany or Japan or China, but increased productivity (yes, IPE is more complicated than that so I am simplifying).Trump's views on NYC as a haven for crime is also outdated, as he seems to remember the NYC of the 1970s or 1980s. This is kind of strange since he spent so much time since then in the construction trade, where one would maybe get a clue about changes in "bad neighborhoods" and all that.

But Trump does not update his priors--he does not learn (he is a lousy Bayesian, overeducated social science types might say). The only thing he learns or adapts to is when a line works in a speech and gets applause, and then he sticks to it. So, when trying to figure out how Trump sees the world, imagine what he saw (via racist lenses and without the benefit of reading anything more complicated than a listicle) in 1984 or so. That is how he views the world today.