Guilty. With the Malaysian plane crashing in the Ukrainian war zone, it is easy to start blaming folks. It may not be the Russian separatists. It might not have been shot down by missiles. Lots of stuff could have happened. So, I am going to speculate anyway because that is what we do either implicitly or explictly. I prefer to be explicit.

What we do know is that commercial aircraft were flying over/thru a war zone. This should be the first WTF question. The Ukrainians said that they would not fire at any planes over 7800m apparently. How reassuring is that? The FAA decided months ago, before there were a series of planes (and helicopters) shot down in the region, to ban American planes/pilots from flying through this area [or not, see comments]. Why didn't other authorities (Dutch, Malaysian, European, ICAO) re-direct flights from here? We know, thanks to the Vincennes disaster, that commercial planes flying over a war zone might be confused for something else.

Some might say that something else caused this plane to fall out of the sky: bomb, pilot error, malfunction. But given that the plane crashed in an area where anti-aircraft activities had been quite energetic and relatively successful, I think Occam's razor would cut all but the missile explanations. Three different sets of actors could have launched a missile to this height--about 33k feet or 10km: Russia, Ukraine, and the Russian separatists. All had access to weapon systems designed to knock down high flying planes. Ukraine inherited Russia's anti-aircraft technology when it split from the Soviet Union. The separatists apparently captured Ukraine's systems (the web is chock full of pics and claims on social media by the separatists that they had these missiles). And Russia has what Russia has.

It is very unlikely that Russia would have shot down this plane. No rational reason to do so (would only escalate a conflict that they have been kind of hoping to go onto the back burner), and unlikely to accidentally shoot down a plane over Ukrainian territory. The separatists and their fellow travelers might blame the Ukraine government for staging such an event. Again, this is unlikely as things were more or less moving in Ukraine's direction lately with some victories on the ground. Why cause a major international crisis and hope that the other sides gets the blame? That is a very dangerous game, and unlikely when, again, things were not getting worse but potentially better for Ukraine.

The separatists? Well, knocking down planes and helicopters has been its primary means of imposing costs on Ukraine. With significant losses of territory, offensive land operations seem not to be a good option to make Ukraine hurt. But knock down expensive and very visible symbols of Ukrainian military might (relatively speaking)? Yes, that makes sense. So, if I had to bet, I would bet that the separatists did this by mistake. They wanted to shoot down Ukrainian military aircraft and had gotten pretty good at it. Governments try harder, usually, to avoid such mistakes, but then again the US shot down an Iranian passenger jet in 1988, the Soviet Union shot down a South Korean plane om 1983 and so on...

Will we find out the truth? Probably. There are far more intel assets dedicated to watching this part of the world than the waters to the west of Australia. Will everyone buy into the explanation with the best evidence? Probably not. I mean, if tweets touting the success of shooting down a transport plane are being erased, then denying reality is likely to be the order of the day.

Again, I could be wrong about all of this. So take all of this with a large grain of salt.

International Relations, Ethnic Conflict, Civil-Military Relations, Academia, Politics in General, Selected Silliness

Thursday, July 17, 2014

Wednesday, July 16, 2014

Illuminati Music?

Weird Al is releasing a video a day this week and next, and it has been wonderous. Using Happy to do Tacky was a nice start. Then a lesson about grammar. And now, some uses of Foil:

I love how this moves from a cooking show into a conspiracy theory extravaganza complete with Patton Oswalt and Tom Lennon.

Plus I love a good Illuminati reference.

I love how this moves from a cooking show into a conspiracy theory extravaganza complete with Patton Oswalt and Tom Lennon.

Plus I love a good Illuminati reference.

Responsibility to Protect Indeed: Srebrenica Continued

A Dutch court ruled that Dutch peacekeepers were partially responsible for the deaths of more than 300 Bosnians when the Srebrenica "safe haven" was attacked by Bosnian Serbs in 1995. This is not anything particularly new as the Netherlands has taken its responsibility in this matter far more seriously than pretty much everyone else.

In 2002, the Dutch government fell after its entire cabinet resigned due to a report on events in Srebrenica seven years earlier. Can you imagine an American or Canadian or British government reacting to events seven years earlier after a critical report is released? No. I didn't think so. Has anyone in Belgium resigned in the aftermath of Rwanda?

The Netherlands developed a series of reforms to try to prevent a similar disaster in the future. Among these reforms are the Article 100 process where the parties in parliament must approve of a letter that explains the purposes and the means of a military deployment before the troops are sent. This is an incredibly transparent process--pretty handy for the researcher that happens to be in town the week this is going on. It might mean too much legislative influence on what actually goes into a military deployment (don't send tanks, they are too aggressive looking), but the letter requires a clear statement of purpose, clarity about the rules of engagement and so on.

This latest ruling is consistent with a previous one--that the Netherlands is responsible for those Bosnian Muslims who had been in the UN compound (that the Dutch had been staffing) and who then were expelled. The courts have ruled that the Dutch are not responsible for those that never made it into the compound.

As I wrote earlier about a similar case, there is plenty of blame to go around. Obviously, the actual killers are mostly responsible, with the International Criminal Tribunal on Yugoslavia taking those cases, including Ratko Mladic, the commander of the genocidaires. Canada neatly dodged responsibility, as the Canadians had peacekeepers in Srebrenica before the Dutch but re-deployed because they saw what was going to happen and didn't want to be around.

The United Nations perhaps cannot get sued, but, in my mind, it has more responsibility than anyone besides the Bosnian Serbs in this case. The Dutch peacekeepers were willing to fight, but needed air support since they were outmanned. At the time, the NATO planes that could be sent were subject to a dual-key system. Any decision to drop bombs required approval from both the local NATO representative and the UN Secretary General's special representative, and the UN rep said no.

The lesson to be learned? Well, the Dutch learned to always bring their own airpower when they deploy, so that they can get the support they need even if the international organizations say no. That's right--the Netherlands would de-flag their planes and fight under the command of the Dutch if their multilateral bosses were to get in the way. Which is why we saw something very strange from 2011-2014--the Dutch police training mission included F-16's....

The articles on this suggest that the prospect of lawsuits might cause countries to decline participation in peacekeeping efforts. Maybe, but there are already enough deterrents to participation in such efforts, including the lesson learned from Somalia and Rwanda--that the "bad guys" may first try to kill the peacekeepers so that they go home.

What this case really reminds us is that the notion of responsibility to protect carries a very heavy burden, which is perhaps why the reality is that most countries tend not to actually bear the responsibility at all.

In 2002, the Dutch government fell after its entire cabinet resigned due to a report on events in Srebrenica seven years earlier. Can you imagine an American or Canadian or British government reacting to events seven years earlier after a critical report is released? No. I didn't think so. Has anyone in Belgium resigned in the aftermath of Rwanda?

The Netherlands developed a series of reforms to try to prevent a similar disaster in the future. Among these reforms are the Article 100 process where the parties in parliament must approve of a letter that explains the purposes and the means of a military deployment before the troops are sent. This is an incredibly transparent process--pretty handy for the researcher that happens to be in town the week this is going on. It might mean too much legislative influence on what actually goes into a military deployment (don't send tanks, they are too aggressive looking), but the letter requires a clear statement of purpose, clarity about the rules of engagement and so on.

This latest ruling is consistent with a previous one--that the Netherlands is responsible for those Bosnian Muslims who had been in the UN compound (that the Dutch had been staffing) and who then were expelled. The courts have ruled that the Dutch are not responsible for those that never made it into the compound.

As I wrote earlier about a similar case, there is plenty of blame to go around. Obviously, the actual killers are mostly responsible, with the International Criminal Tribunal on Yugoslavia taking those cases, including Ratko Mladic, the commander of the genocidaires. Canada neatly dodged responsibility, as the Canadians had peacekeepers in Srebrenica before the Dutch but re-deployed because they saw what was going to happen and didn't want to be around.

The United Nations perhaps cannot get sued, but, in my mind, it has more responsibility than anyone besides the Bosnian Serbs in this case. The Dutch peacekeepers were willing to fight, but needed air support since they were outmanned. At the time, the NATO planes that could be sent were subject to a dual-key system. Any decision to drop bombs required approval from both the local NATO representative and the UN Secretary General's special representative, and the UN rep said no.

The lesson to be learned? Well, the Dutch learned to always bring their own airpower when they deploy, so that they can get the support they need even if the international organizations say no. That's right--the Netherlands would de-flag their planes and fight under the command of the Dutch if their multilateral bosses were to get in the way. Which is why we saw something very strange from 2011-2014--the Dutch police training mission included F-16's....

The articles on this suggest that the prospect of lawsuits might cause countries to decline participation in peacekeeping efforts. Maybe, but there are already enough deterrents to participation in such efforts, including the lesson learned from Somalia and Rwanda--that the "bad guys" may first try to kill the peacekeepers so that they go home.

What this case really reminds us is that the notion of responsibility to protect carries a very heavy burden, which is perhaps why the reality is that most countries tend not to actually bear the responsibility at all.

Tuesday, July 15, 2014

Keeping Religion in Ethnicity

When I posted a few days ago about the Israel-Palestinian conflict, a friend asked about my including of religion in the definition of ethnic conflict. So, here is my explanation.

The definition of ethnicity that people in political science tend to use focuses on perceived common ancestry centering around a few markers of identity. The definition in my dissertation and first book:

Folks who study ethnicity are very aware that it is a socially constructed thing, so the boundaries are fuzzy and one's identity is not entirely up to oneself but how other see it. Note number 2 of the AMAR criteria--that the membership is defined by members and nonmembers--not by oneself.

For me, in my research, religion does much of the same causal work as language or race or kinship--creating a sense of affinity or enmity which then affects policy preferences--do we want to help group x or group y? Let's help the group with whom we share some ties--racial, religious, regional, kinship, or linguistic. When identities cross-cut, then politics is about defining which ties are the most salient. When identities converge--group x shares the same religion, language and race as group y--the politics became easier. It becomes less about defining which identity matters and more about defining oneself as the best defender of the group.

Which leads us to ethnic outbidding. When politicians compete to be the best defender of group x, each one may try to top the other, as in an auction for support from the group. The claims become more and more radical. Religious outbidding and linguistic outbidding are not that different--just the promises will vary.

For my work, the key difference between religion and other ethnic identities is really about the reach. That religious identities cross not just land borders but across oceans so that Libya supported the Moros of the Philippines, for instance. Race can have the same distance, but clan/tribe and language much less.

Each kind of ethnic tie will have different implications for politics, as I discussed early in my blogging career. Religious differences have implications for much of what governments do, whereas linguistic divides matter for employment and education more so than elsewhere. Race? The irony here is that race does not really have much in the way of logical implications for politics until/unless racial divisions have historical content. And yes, then it matters quite a bit.

Anyhow, a long answer to a simple question. When we speak of ethnic groups, ethnic ties, ethnicity in poli sci, the concept includes religion as a potentially relevant component. Why? Because it is how people identify us and them in social groups that sometimes become politically relevant.

The definition of ethnicity that people in political science tend to use focuses on perceived common ancestry centering around a few markers of identity. The definition in my dissertation and first book:

"Ethnic groups are 'collective groups whose membership is largely determined by real or putative ancestral inherited ties, and who perceive these ties as systematically affecting their place and fate in the political and socioeconomic structures of their state and society (Rothschild 1981).' These ties usually are related to race, kinship (tribe or clan), religion and language."In the intervening years, not much has changed. In a forthcoming piece of which I am one of many co-authors, the focus is very much on defining what counts and what does not count for the dataset:

Consequently, the AMAR criteria that aim to outline socially relevant groups at a given point in time are that:Why is religion part of ethnic identity when we see so often people refer to "ethnic and religious" or "ethnoreligious"? Because it is about identity and one that is seen as inherited. Sure, people can convert to a different religion, but other "markers" of identity are also more malleable than advertised. Languages can be learned and adopted. One can move to a different region and then identify with that region (I am reminded of the "Californian since 1970 or 1980 bumper stickers"). One could argue that race is fixed, but yet not so much as people of mixed race can try to identify in a variety of ways. Kinship often means multiple identities as well.

(1) Membership in the group is determined primarily by descent by both members and non-members.

(2) Membership in the group is recognized and viewed as important by members and/or nonmembers. The importance may be psychological, normative, and/or strategic.

(3) Members share some distinguishing cultural features, such as common language, religion, occupational niche, and customs.

(4) One or more of these cultural features are either practiced by a majority of the group or preserved and studied by a set of members who are broadly respected by the wider membership for so doing.

(5) The group has at least 100,000 members or constitutes 1% of a country’s population.

Folks who study ethnicity are very aware that it is a socially constructed thing, so the boundaries are fuzzy and one's identity is not entirely up to oneself but how other see it. Note number 2 of the AMAR criteria--that the membership is defined by members and nonmembers--not by oneself.

For me, in my research, religion does much of the same causal work as language or race or kinship--creating a sense of affinity or enmity which then affects policy preferences--do we want to help group x or group y? Let's help the group with whom we share some ties--racial, religious, regional, kinship, or linguistic. When identities cross-cut, then politics is about defining which ties are the most salient. When identities converge--group x shares the same religion, language and race as group y--the politics became easier. It becomes less about defining which identity matters and more about defining oneself as the best defender of the group.

Which leads us to ethnic outbidding. When politicians compete to be the best defender of group x, each one may try to top the other, as in an auction for support from the group. The claims become more and more radical. Religious outbidding and linguistic outbidding are not that different--just the promises will vary.

For my work, the key difference between religion and other ethnic identities is really about the reach. That religious identities cross not just land borders but across oceans so that Libya supported the Moros of the Philippines, for instance. Race can have the same distance, but clan/tribe and language much less.

Each kind of ethnic tie will have different implications for politics, as I discussed early in my blogging career. Religious differences have implications for much of what governments do, whereas linguistic divides matter for employment and education more so than elsewhere. Race? The irony here is that race does not really have much in the way of logical implications for politics until/unless racial divisions have historical content. And yes, then it matters quite a bit.

Anyhow, a long answer to a simple question. When we speak of ethnic groups, ethnic ties, ethnicity in poli sci, the concept includes religion as a potentially relevant component. Why? Because it is how people identify us and them in social groups that sometimes become politically relevant.

Monday, July 14, 2014

Deceptive Numbers, 473th Edition

Bernie Sanders, the Senator from Vermont, has been raising a stink about how the veterans have been treated. And good for him for doing so. We need to take care of those who were put in harm's way. But he is getting his numbers wrong:

The six trillion dollar estimate for the Iraq/Afghanistan wars include not just the salaries from 2001-2016 (or whatever), the fuel, the logistics, and all that, but also .... the cost of taking care of the veterans from now until they die.

I was at a talk at a recent APSA by Linda Blimes who presented a series of graphs depicting the costs of wars. It turns out, if I remember correctly, that the U.S. is still paying some of the costs of World War I, and the annual costs peaked in the 1970s (I think). That the costs of WWII are still quite significant, as the U.S. is paying the medical care of the veterans of that war. The costs of Vietnam will be with us for quite a while. The veterans who fought in Iraq and Afghanistan will be living for another sixty years at least. So, the six trillion dollar figure is based on the costs of the wars AND the costs of taking care of the vets.

The key point may be that we are not treating the vets well right now (the VA controversy is a mess of conflicting reports, but this quote is just deceptive. If Sanders does not know the source of the estimate, then he is not doing his job. There are good arguments to be made about the treatment of vets, but $6 trillion vs a few billion is not one of them.

The six trillion dollar estimate for the Iraq/Afghanistan wars include not just the salaries from 2001-2016 (or whatever), the fuel, the logistics, and all that, but also .... the cost of taking care of the veterans from now until they die.

I was at a talk at a recent APSA by Linda Blimes who presented a series of graphs depicting the costs of wars. It turns out, if I remember correctly, that the U.S. is still paying some of the costs of World War I, and the annual costs peaked in the 1970s (I think). That the costs of WWII are still quite significant, as the U.S. is paying the medical care of the veterans of that war. The costs of Vietnam will be with us for quite a while. The veterans who fought in Iraq and Afghanistan will be living for another sixty years at least. So, the six trillion dollar figure is based on the costs of the wars AND the costs of taking care of the vets.

The key point may be that we are not treating the vets well right now (the VA controversy is a mess of conflicting reports, but this quote is just deceptive. If Sanders does not know the source of the estimate, then he is not doing his job. There are good arguments to be made about the treatment of vets, but $6 trillion vs a few billion is not one of them.

Side Effects of Realpolitik

Dan Drezner has a fun post today: what if Realism was advertised like a prescription drug?

I have one problem with it--the list of side effects is too short:

I have one problem with it--the list of side effects is too short:

Possible side effects of Realaxil include a waning interest in other people’s problems. Do not take Realaxil if you care at all about how other countries conduct their own affairs. Realaxil can cause drowsiness or forgetfulness when operating heavy military machinery. Please consult your lawyer to see if taking Realaxil will conflict with pre-existing commitments to protect friends or partners during times of emergency.I would say that the other dangers of taking Realaxil are:

- the tendency to dismiss the relevance of domestic politics---yours or others.

- overconfidence in the clarity of the imperatives of the international system--one tends to think that there is one obvious best way to react to an international shock or pressure.

- an exaggerated sense of one's own importance--bad policy happens because people didn't listen to those taking realaxil.

Advanced Analytics in Ultimate

It was only a matter of time. Apparently, folks are trying to bring the sabermetric revolution to ultimate frisbee (H/T to Dan Drezner). Ultimate has gotten increasingly serious over the course of my time playing the sport. The people who start playing in college now have been playing for years and are far more athletic than when I started. There are now a couple of professional leagues in the US, regular world championships with a fair amount of representation from around the globe, an 11th edition of the rules, and so on.

Indeed, one of the newest rules is somewhat counter to the old spirit of the game. It used to be that if you committed a foul, you would call it on yourself. However, at the most competitive levels, this became a trick that a player could do to stop play if his/her team was out of position. I even got into a mild argument last week because I told the player I was guarding that he might want to call a foul on me (I had kicked his hand trying to block the disk he was throwing), and he said I should call it. I eventually explained that the rules had changed....

Anyhow, the idea that we can learn about how to play better via more data makes complete sense. I had one team that did try to collect stats--they would audio-tape play by play so that we could count how many passes someone threw well or errantly, how many dropped passes we would have (I compensate for a lack of speed/height by very rarely dropping the disk #humblebrag), how many defensive plays were made and so on.

The WSJ story focuses on the usual stuff--how to measure which players contribute the most--but also strategy.

The funny thing is that teams in rec leagues and even many teams that compete at tourneys kind of suck at dumping the disk. It is not a hard pass if the two players are committed to it, but one is often distracted by the fleeting temptation to throw the disk up the field. Again, the good teams do this quite well.

The article's story about the NY team that does not score enough when close hits home with me, as I have played with many teams that are good for most of the field but then turn it over when close to scoring. It is not only frustrating but can be game-breaking.

There is far more that can be figured out--like which kinds of zone defenses work the best, which kinds of offensive plays are more or less successful, does breaking the mark (throwing to the side of the field the opponent is trying to take away) as rewarding as it seems to be?

Just as baseball has this finite thing that has become the obsession--outs which limit the opportunities, ultimate has something pretty basic too--turnovers. The team that turns over the disk less wins. So, I think the ulti-metrics should focus on exactly that question--the causes and prevention of turnovers.

We live in interesting times...

Indeed, one of the newest rules is somewhat counter to the old spirit of the game. It used to be that if you committed a foul, you would call it on yourself. However, at the most competitive levels, this became a trick that a player could do to stop play if his/her team was out of position. I even got into a mild argument last week because I told the player I was guarding that he might want to call a foul on me (I had kicked his hand trying to block the disk he was throwing), and he said I should call it. I eventually explained that the rules had changed....

Anyhow, the idea that we can learn about how to play better via more data makes complete sense. I had one team that did try to collect stats--they would audio-tape play by play so that we could count how many passes someone threw well or errantly, how many dropped passes we would have (I compensate for a lack of speed/height by very rarely dropping the disk #humblebrag), how many defensive plays were made and so on.

The WSJ story focuses on the usual stuff--how to measure which players contribute the most--but also strategy.

Mr. Childers and Mr. Weiss crunched the numbers and were able to prove, for example, that if a player has the Frisbee in a corner close to his own end zone, then the optimal pass is actually a backward pass to the middle of the field, even if doing that seems counterproductive.This is actually far from counter-intuitive, but glad that we have data that backs up a conventional wisdom: tis better to move the disk to the middle of the field, even by going backwards, than stay stuck along one sideline. I have long observed that teams that move the disk laterally do far better than those that do not. The terms vary--in the US and Quebec it is called dumping and in Ontario and beyond it seems to be called bailing--but the idea is the same. You can only hold onto the disk for 8-10 seconds [the opponent marking the person with the disk calls out 1 2 3 and so on--some say mississippi, some say steamboat (Canada/English) or bateau (Canada French)], so you have to keep the disk moving and throwing it backwards or sideways re-sets the stall count again and again.

The funny thing is that teams in rec leagues and even many teams that compete at tourneys kind of suck at dumping the disk. It is not a hard pass if the two players are committed to it, but one is often distracted by the fleeting temptation to throw the disk up the field. Again, the good teams do this quite well.

The article's story about the NY team that does not score enough when close hits home with me, as I have played with many teams that are good for most of the field but then turn it over when close to scoring. It is not only frustrating but can be game-breaking.

There is far more that can be figured out--like which kinds of zone defenses work the best, which kinds of offensive plays are more or less successful, does breaking the mark (throwing to the side of the field the opponent is trying to take away) as rewarding as it seems to be?

Just as baseball has this finite thing that has become the obsession--outs which limit the opportunities, ultimate has something pretty basic too--turnovers. The team that turns over the disk less wins. So, I think the ulti-metrics should focus on exactly that question--the causes and prevention of turnovers.

We live in interesting times...

Fearing Parliamentarism? Afghanistan's Potential Institutional Reform

The news today out of Afghanistan is that the competitors for the presidency have agreed to move the political system towards a parliamentary system. That the loser becomes chief executive and then in a couple of years, they will modify the constitution to create a more semi-presidential system with a Prime Minister serving as head of the government.

This essentially does one of Afghanistan's original sins: centralizing too much power within the Presidency. The story suggests that the Americans feared the instability of a parliamentary system. I guess that is what happens when Americans help draw up the constitution, as American politicians have no experience with parliamentarism. I am not sure what kind of instability they are thinking of, as I don't think parliamentary systems are associated with coups. And I am sure that parliamentarism is no worse than presidentialism when it comes to ethnic strife.

Presidentialism vs. parliamentarism has been much debated by scholars of comparative politics. There are many flaws in presidentialism, but the key is that putting all the power in one person's hands makes it very hard to share, and means that elections are winner take all. Parliamentary systems can be like that or not, depending on the electoral system. Proportional representation turns out to be the key (at least for managing ethnic conflict), as it means that minorities can gain meaningful access to the political system. And if the population is diverse enough, to govern, one needs to form coalitions. This might be the "instability" that is spoken of in the NYT article, but there are plenty of stable parliamentary systems.

So, as one twitter friend put it,

Anyhow, re-thinking the institutions that govern the Afghan political system might actually lead to actual governing of Afghanistan.... That is, the reach of the government has been limited by the war. Developing a better design might help reduce the support for violence. Of course, it might also be a bit late in the game.

A key irony here is that the area experts and the comparativists probably see eye to eye on this: the institutions set up by the outsiders were poorly designed--they did not fit the Afghan context (too centralized) and they did not reflect the lessons of extensive scholarship on post-conflict (semi) democratic institution building. South Africa, for all of its current challenges, is far better off having listened to the contending experts on how best to design democratic institutions. Not sure why these folks were ignored in 2002-2004.

As always, it goes back to the noted political philosopher Jeff Spicoli:

This essentially does one of Afghanistan's original sins: centralizing too much power within the Presidency. The story suggests that the Americans feared the instability of a parliamentary system. I guess that is what happens when Americans help draw up the constitution, as American politicians have no experience with parliamentarism. I am not sure what kind of instability they are thinking of, as I don't think parliamentary systems are associated with coups. And I am sure that parliamentarism is no worse than presidentialism when it comes to ethnic strife.

Presidentialism vs. parliamentarism has been much debated by scholars of comparative politics. There are many flaws in presidentialism, but the key is that putting all the power in one person's hands makes it very hard to share, and means that elections are winner take all. Parliamentary systems can be like that or not, depending on the electoral system. Proportional representation turns out to be the key (at least for managing ethnic conflict), as it means that minorities can gain meaningful access to the political system. And if the population is diverse enough, to govern, one needs to form coalitions. This might be the "instability" that is spoken of in the NYT article, but there are plenty of stable parliamentary systems.

So, as one twitter friend put it,

@smsaideman It's cute when we take credit for unscrewing what was our fault in the first place.Of course, the shift from presidentialism to something else (again, my suspicion is that it will be a mix or semi-presidentialism especially as whoever is president is not going to give away all of his power) misses a key flaw in the system--presidential and parliamentary systems can be too centralized. What is needed is some kind of federalism. People fear that federalism leads to secession, but that depends on how the federalism is designed and on other stuff as well. But having the folks in Kabul call the shots all the way down to choosing who runs each district has clearly been problematic. Federalism can be complicated less because of the secession problem and more because the local majorities may abuse the local minorities.

— Gary Owen (@ElSnarkistani) July 14, 2014

Anyhow, re-thinking the institutions that govern the Afghan political system might actually lead to actual governing of Afghanistan.... That is, the reach of the government has been limited by the war. Developing a better design might help reduce the support for violence. Of course, it might also be a bit late in the game.

A key irony here is that the area experts and the comparativists probably see eye to eye on this: the institutions set up by the outsiders were poorly designed--they did not fit the Afghan context (too centralized) and they did not reflect the lessons of extensive scholarship on post-conflict (semi) democratic institution building. South Africa, for all of its current challenges, is far better off having listened to the contending experts on how best to design democratic institutions. Not sure why these folks were ignored in 2002-2004.

As always, it goes back to the noted political philosopher Jeff Spicoli:

"if we don't get some cool rules ourselves, pronto, we'll just be bogus, too."

Sunday, July 13, 2014

A Pox On Both Their Houses?

I don't write much on Israel-Palestine. Never have. I have one piece in an edited volume--and it is the conclusion. I have had a few PhD students who work on that part of the world. Otherwise, I avoid the topic like a plague despite having worked on ethnic conflict all my career (and religion is included in my definition of ethnicity by the way). Why? Is it because a brief speculation about how my stuff applied blew up in my face at my second job talk? Probably not.

Is it because some impossible problems are so frustrating that it hurts to think about them? Maybe.

All I know is that the status quo sure as hell seems unsustainable for Israel and probably for the Palestinians. The old mantra that Israel can be democratic or Jewish but not both seems to becoming true. The leadership of both sides have not covered themselves in glory for the couple of decades.

And now the politics is getting more self-destructive. The more people settled in the West Bank means that there are more voters in the West Bank, which then creates more political heft for those who want more settlements. This creates a built in lobby for ... irredentism. Yes, enlarging the state of Israel to include more and more of the West Bank is irredentism. And the problem for Israel is what happens when you include all of this territory in the political system--with the Palestinians who reside in these areas?

I have not followed the situation so closely to understand what is going on with Hamas, but I would imagine that an inability to deliver the goods of governance might lead to a greater dependence on symbolic politics and on provoking Israel.

I am confused about much stuff. For instance, the initial story that has now exploded into renewed conflict was about a few Jewish kids being kidnapped and then killed. The coverage makes it sound like this was Hamas strategy. But was it? Does Hamas control all violence aimed at the Israelis? Probably not. Just as the initial violence responding to the teens' deaths was not state-sponsored either. Indeed, the loss of control over the process is an inevitable part of this, as the prolonged nature of the conflict leaves many on all sides dissatisfied with how their leaders are handling it.

What is the U.S. to do? Not sure. The Obama Administration has entered these waters a couple of times, and have had little gained from it. Netanyahu has done his best to crap all over Obama, so the U.S. has little ability to shape Israel's responses. This would be a bad time to cut the flow of dollars to Israel, but I wish Obama had taken a stronger stand earlier when Netanyahu kept building more settlements. But, again, Netanyahu has his own political games at home that trump outside pressure or the long term costs.

And this is why I don't write about this conflict--too depressing, too frustrating, and too unlikely to get resolved anytime soon.

Is it because some impossible problems are so frustrating that it hurts to think about them? Maybe.

All I know is that the status quo sure as hell seems unsustainable for Israel and probably for the Palestinians. The old mantra that Israel can be democratic or Jewish but not both seems to becoming true. The leadership of both sides have not covered themselves in glory for the couple of decades.

And now the politics is getting more self-destructive. The more people settled in the West Bank means that there are more voters in the West Bank, which then creates more political heft for those who want more settlements. This creates a built in lobby for ... irredentism. Yes, enlarging the state of Israel to include more and more of the West Bank is irredentism. And the problem for Israel is what happens when you include all of this territory in the political system--with the Palestinians who reside in these areas?

I have not followed the situation so closely to understand what is going on with Hamas, but I would imagine that an inability to deliver the goods of governance might lead to a greater dependence on symbolic politics and on provoking Israel.

I am confused about much stuff. For instance, the initial story that has now exploded into renewed conflict was about a few Jewish kids being kidnapped and then killed. The coverage makes it sound like this was Hamas strategy. But was it? Does Hamas control all violence aimed at the Israelis? Probably not. Just as the initial violence responding to the teens' deaths was not state-sponsored either. Indeed, the loss of control over the process is an inevitable part of this, as the prolonged nature of the conflict leaves many on all sides dissatisfied with how their leaders are handling it.

What is the U.S. to do? Not sure. The Obama Administration has entered these waters a couple of times, and have had little gained from it. Netanyahu has done his best to crap all over Obama, so the U.S. has little ability to shape Israel's responses. This would be a bad time to cut the flow of dollars to Israel, but I wish Obama had taken a stronger stand earlier when Netanyahu kept building more settlements. But, again, Netanyahu has his own political games at home that trump outside pressure or the long term costs.

And this is why I don't write about this conflict--too depressing, too frustrating, and too unlikely to get resolved anytime soon.

Friday, July 11, 2014

Bad Military Argument Week?

Something seemed to become a trend this week--really dumb arguments about Canadian defence stuff. Part of it was the timing of when I read stuff as opposed to it being published this week, but as a card-carrying member of the military-industrial-academic complex, I am embarrassed.

Before I get going, I need to make my biases clear:

While the author is correct that Canada would barely make a dent in a US-China or a US-Russia war, having an advanced aircraft would be handy against lesser opponents as anti-aircraft weapons spread.

I also happened to read anti- and pro-Canadian sub arguments that contained some similar doozies.

The pro-sub argument, by Paul Mitchell, starts from a very weak spot: challenging the lemon reputation of the current Victoria class subs: "largely because of a series of unfortunate incidents." Holy Lemony Snicket! That the subs in 2013 had something like 265 operational days at sea might sound impressive if that were the average per sub, but that was the total for all four subs. That is, the subs averaged less than seventy days at sea each. The article blames it on tight budget constraints, but it is obviously more than that. Plus if you cannot operate under tight budget constraints, then good luck as those constraints are not going away. Indeed, my primary argument against Canadian subs is that the budgets are and will always be tight, so that the capability will never be enough to be more than symbolic. And lots of money for symbolic capability would be fine if there not serious tradeoffs ahead.

That the subs share features with British nuclear subs is seen as a feature, a plus, when it turns out that this bit of reality meant that the British would not share much info with the Canadians about the subs and how to fix them.

Much of the debate about subs, like about planes, is whether they can help out in the far north. These subs cannot breathe under the ice, alas (nuclear subs can and some with special systems but Canada can't afford them any time soon). The good news, according to the author, is that the arctic will be ice free so who needs to breathe under the ice? The problem is that by the time the ice is gone, the subs will be too. They simply will not last beyond 2030 without a heap of luck and duck tape. And that drives home the real problem. The main argument for keeping Canada in the sub business is that once out of it, it is hard to get back in. But my guess is that Canada will be out eventually anyway. The next batch of subs will be far more expensive than the current batch, because that is how military inflation works especially when one does not manage procurement well. So, will Canada invest in six or eight new subs? No. Four? Maybe, but then we are stuck with a purely symbolic force again.

The main claim to keep subs is to stay in the intel sharing business with the US, but that seems like something that can be negotiated regardless of subs or no subs. The funny thing is that the article takes shots at the anti-sub argument's take on UAVs and ignores the other possibility--underwater unmanned vehicles. They exist and will be developed much further. Why not invest in those and not in more subs?

The best arguments for subs are mostly that some of the anti-sub arguments, by Michael Byers, are quite lame. For instance, arguing that China might be deterred from war due to its dependence on international trade is amusing/ironic/historically blind. Japan was quite dependent on international trade--especially oil and iron from the US--before WWII and yet went to war. It turned out that its need for imports became a huge weakness as American subs destroyed most of the Japanese merchant fleet.

Ultimately, I side with Byers not because I don't think subs can be handy. They can be. I just don't think that the benefits of having a symbolic fleet of four semi-broken subs are worth the cost in a time of flat/declining defence budgets. I don't expect Canada to ever be that serious about investing in subs. If they were to do so, then it would mean cutting elsewhere, and that is a tradeoff that the Canadian defense establishment refuses to face.

Regarding the F-35, I am still unsure. I tend to think the Super Hornet is a better idea because it is a proven technology. While there will not be the same economies of scale in the upkeep down the road, I am guessing it will need less upkeep than a plane that is being produced even as it is being tested. Of course, I could be completely wrong, and Canada might start buying French stuff.

Before I get going, I need to make my biases clear:

- I am ambivalent about the F-35--it is too expensive and not that good of a plane but the alternatives are none too spiffy.

- On the other hand, I love subs. I spent much time in my teens and then since reading about the real exploits of American subs in Pacific during WWII and fictional exploits during/after the cold war.

- I am often seen as a hawk because I think that militaries are instruments of national policy.

- I am often seen as a dove because I am skeptical about the use of force--it has limited utility.

"New Canadian fighters would almost certainly never be involved in serious strike or aerial combat operations"Um, the current batch of fighters participated in the aerial campaign against Serbia in 1999 and over Libya in 2011. Given the likelihood that air power will be the first step in any future NATO effort anywhere, it is likely that strike aircraft of some kind will be the asset that NATO commanders will seek to deploy.

"The only credible aerial threat to Canadian territory, sovereignty and populace is a copy-cat “9/11” attack – a danger that essentially cannot be defeated by fighter aircraft."Actually, fighter aircraft are exactly what you want to have to trail a hijacked airliner and even, dare I say it, shoot one down if necessary.

While the author is correct that Canada would barely make a dent in a US-China or a US-Russia war, having an advanced aircraft would be handy against lesser opponents as anti-aircraft weapons spread.

"Fighters simply cannot contribute anything substantial toward the achievement of the six Canadian defence objectives."While I agree that Canada needs to re-assess the objectives and prioritize, fighter planes would be handy for three of the priorities--NORAD/continental ops, respond to terrorist attack, lead/conduct major international operation, deploy forces in reponse to crises elsewhere in the world. The last perfectly describes the current Canadian deployment to Romania and its turn in the Baltic Air patrol this fall.

I also happened to read anti- and pro-Canadian sub arguments that contained some similar doozies.

The pro-sub argument, by Paul Mitchell, starts from a very weak spot: challenging the lemon reputation of the current Victoria class subs: "largely because of a series of unfortunate incidents." Holy Lemony Snicket! That the subs in 2013 had something like 265 operational days at sea might sound impressive if that were the average per sub, but that was the total for all four subs. That is, the subs averaged less than seventy days at sea each. The article blames it on tight budget constraints, but it is obviously more than that. Plus if you cannot operate under tight budget constraints, then good luck as those constraints are not going away. Indeed, my primary argument against Canadian subs is that the budgets are and will always be tight, so that the capability will never be enough to be more than symbolic. And lots of money for symbolic capability would be fine if there not serious tradeoffs ahead.

That the subs share features with British nuclear subs is seen as a feature, a plus, when it turns out that this bit of reality meant that the British would not share much info with the Canadians about the subs and how to fix them.

Much of the debate about subs, like about planes, is whether they can help out in the far north. These subs cannot breathe under the ice, alas (nuclear subs can and some with special systems but Canada can't afford them any time soon). The good news, according to the author, is that the arctic will be ice free so who needs to breathe under the ice? The problem is that by the time the ice is gone, the subs will be too. They simply will not last beyond 2030 without a heap of luck and duck tape. And that drives home the real problem. The main argument for keeping Canada in the sub business is that once out of it, it is hard to get back in. But my guess is that Canada will be out eventually anyway. The next batch of subs will be far more expensive than the current batch, because that is how military inflation works especially when one does not manage procurement well. So, will Canada invest in six or eight new subs? No. Four? Maybe, but then we are stuck with a purely symbolic force again.

The main claim to keep subs is to stay in the intel sharing business with the US, but that seems like something that can be negotiated regardless of subs or no subs. The funny thing is that the article takes shots at the anti-sub argument's take on UAVs and ignores the other possibility--underwater unmanned vehicles. They exist and will be developed much further. Why not invest in those and not in more subs?

The best arguments for subs are mostly that some of the anti-sub arguments, by Michael Byers, are quite lame. For instance, arguing that China might be deterred from war due to its dependence on international trade is amusing/ironic/historically blind. Japan was quite dependent on international trade--especially oil and iron from the US--before WWII and yet went to war. It turned out that its need for imports became a huge weakness as American subs destroyed most of the Japanese merchant fleet.

Ultimately, I side with Byers not because I don't think subs can be handy. They can be. I just don't think that the benefits of having a symbolic fleet of four semi-broken subs are worth the cost in a time of flat/declining defence budgets. I don't expect Canada to ever be that serious about investing in subs. If they were to do so, then it would mean cutting elsewhere, and that is a tradeoff that the Canadian defense establishment refuses to face.

Regarding the F-35, I am still unsure. I tend to think the Super Hornet is a better idea because it is a proven technology. While there will not be the same economies of scale in the upkeep down the road, I am guessing it will need less upkeep than a plane that is being produced even as it is being tested. Of course, I could be completely wrong, and Canada might start buying French stuff.

Wednesday, July 9, 2014

Re-thinking Next Year's Travel Plans

When this is going around Israel like hotcakes (latkes?), I may have to re-think.

This is a list of bomb shelters and times to "duck and cover" according to the tweet I saw in Israel. Why should I care? Because I am scheduled to teach a short course in Jerusalem next spring. I think I have a basic rule--not to teach anywhere that requires me to know where bomb shelters are.

Sure, I knew before this past week that Israel has a few problems with its neighborhood, and I agreed to do the course knowing that. But it is one thing to think about the possibilities and it is another to have to ponder flying into a war zone. Crap.

Why did I agree to teach a course in Israel? Because I am working on the next project on civil-military relations, and getting a paid trip to hang out in Israel would be most useful for the project. I have never been to the Mideast, other than a brief stay in Dubai on the way to and from Afghanistan. Oh well, I guess I will leave my options open for as long as I can. Time to email Israel.

This is a list of bomb shelters and times to "duck and cover" according to the tweet I saw in Israel. Why should I care? Because I am scheduled to teach a short course in Jerusalem next spring. I think I have a basic rule--not to teach anywhere that requires me to know where bomb shelters are.

Sure, I knew before this past week that Israel has a few problems with its neighborhood, and I agreed to do the course knowing that. But it is one thing to think about the possibilities and it is another to have to ponder flying into a war zone. Crap.

Why did I agree to teach a course in Israel? Because I am working on the next project on civil-military relations, and getting a paid trip to hang out in Israel would be most useful for the project. I have never been to the Mideast, other than a brief stay in Dubai on the way to and from Afghanistan. Oh well, I guess I will leave my options open for as long as I can. Time to email Israel.

Tuesday, July 8, 2014

When Ignorance Is Bliss, Academic Edition

Dan Nexon, editor of ISQ, is seeking feedback from reviewers about stuff that causes reviewers to see red. My fave: when people cite an author as saying x when actually x happens to be the argument they are seeking to criticize or challenge. Sure, I mostly notice it when people cite me wrong, but hey, reading comprehension, people!

Anyhow, this has led to some comments about how knowing more about the reviewing process might just create more anxiety for those submitting articles. If one has to think about every way in which they might be antagonizing reviewers, then potential submitters might find themselves paralyzed. That over-thinking, which is an occupational hazard/requirement, might lead to too much thinking about how to get past the reviewers and not enough thinking about the argument/methods/data/findings itself.

There is a basic tension in much of this stuff, and not just article writing but also the job market--that thinking about the game within the game can distract from thinking about the game itself. One of the problems I have with much of the stuff at Political Science Rumors (aside from the misogyny, racism, and meanness--which can be moderated/deleted) is that the focus is on explaining outcomes that are not about the work.

I get accused of being naive because I tend to think that the work matters, rather than networks, reputation, rankings and all that. I don't think it is only about the work, but I do think that if more time is spent on doing interesting work and making sure that one writes about it in a way that makes it interesting to others, then one is better off.

Still, there is already much thinking about how to game the review process--that there are beliefs about how to cite people to get the "right" reviewers and avoid the "wrong" ones, that there are many beliefs about the process that are just wrong.* That more information about how it really works, even if it creates some anxiety, is surely better than ignorance.

The problem, of course, with much more difficult job markets and increasing tenure standards is that the stakes are high. Which means there is far more fear. And we know what happens when there is more fear:

and yes, I could have used a clip from The Wire "it is all in the game, yo" or something like that but summer is for Star Wars.

Anyhow, this has led to some comments about how knowing more about the reviewing process might just create more anxiety for those submitting articles. If one has to think about every way in which they might be antagonizing reviewers, then potential submitters might find themselves paralyzed. That over-thinking, which is an occupational hazard/requirement, might lead to too much thinking about how to get past the reviewers and not enough thinking about the argument/methods/data/findings itself.

There is a basic tension in much of this stuff, and not just article writing but also the job market--that thinking about the game within the game can distract from thinking about the game itself. One of the problems I have with much of the stuff at Political Science Rumors (aside from the misogyny, racism, and meanness--which can be moderated/deleted) is that the focus is on explaining outcomes that are not about the work.

I get accused of being naive because I tend to think that the work matters, rather than networks, reputation, rankings and all that. I don't think it is only about the work, but I do think that if more time is spent on doing interesting work and making sure that one writes about it in a way that makes it interesting to others, then one is better off.

Still, there is already much thinking about how to game the review process--that there are beliefs about how to cite people to get the "right" reviewers and avoid the "wrong" ones, that there are many beliefs about the process that are just wrong.* That more information about how it really works, even if it creates some anxiety, is surely better than ignorance.

* To be clear, I am not referring to the truly awful citation/review gaming stuff that hit the news today. While it is a bit sketchy to cite key people in your first few paragraphs to try to get those people selected to be your reviewer, it is another order of magnitude to create false accounts so that you can review your own stuff.

The problem, of course, with much more difficult job markets and increasing tenure standards is that the stakes are high. Which means there is far more fear. And we know what happens when there is more fear:

and yes, I could have used a clip from The Wire "it is all in the game, yo" or something like that but summer is for Star Wars.

The Source of the 10% Problem

I have ranted often about the ten percent problem: that a certain percentage of students simply cannot follow instructions. That if I ask those who cannot follow instructions to move to a side of the classroom, they will lay down on the floor, stand on their head or do something else. Only last week did someone suggest that I tell the students who can follow instructions to move. Of course, that would not work either since self-awareness is not a strong suit of those who cannot follow instructions.

Anyway, I realized this is not a teenage or college student problem last week. I attended the orientation at my Frosh Spew's school. They had joint sessions and then the new students went off for their orientation, and the remaining folks (mostly parents but also suffering younger siblings) got to have heaps of presentations about various elements of college life. The Q&A revealed that instruction comprehension and especially its absence is a lifelong thing. There were more than a few parents asking questions that had already been answered, and more than a few parents asking questions that need not be asked. Yes, some good questions were asked as not every presentation was perfect, and there is a lot of room for confusion for parents new to this process.

Much has changed since when we were in college--a lot more resources, a lot more awareness of the complications and stresses, and so on. But when the presenter says: if your child is over 18, then we cannot tell you about their grades or their health circumstances or their finances without a written waiver, then you don't really need to ask: but if my kid is sick, you will tell me, right? Only if it is life threatening. Otherwise, no, the college will not do so. And calls from parents will be re-directed from profs to associate deans--which gives this prof another reason to believe that administrative bloat may not be all that bad.

Oh, and one note on Canadian/American cultural differences: after ultimate last night, I was asked about my trip last week that caused me to miss the last game, and I talked about college. The Canadians pointed out that college means something different up here--mostly technical or vocational schools. Even as most Americans who get BA's get them from universities (size matters), they refer to it as going to college. Which is strange given that American colleges range from junior to community to vocational to liberal arts colleges. Canada does not really have much in the way of liberal arts colleges (there are some near exceptions).

Anyway, I realized this is not a teenage or college student problem last week. I attended the orientation at my Frosh Spew's school. They had joint sessions and then the new students went off for their orientation, and the remaining folks (mostly parents but also suffering younger siblings) got to have heaps of presentations about various elements of college life. The Q&A revealed that instruction comprehension and especially its absence is a lifelong thing. There were more than a few parents asking questions that had already been answered, and more than a few parents asking questions that need not be asked. Yes, some good questions were asked as not every presentation was perfect, and there is a lot of room for confusion for parents new to this process.

Much has changed since when we were in college--a lot more resources, a lot more awareness of the complications and stresses, and so on. But when the presenter says: if your child is over 18, then we cannot tell you about their grades or their health circumstances or their finances without a written waiver, then you don't really need to ask: but if my kid is sick, you will tell me, right? Only if it is life threatening. Otherwise, no, the college will not do so. And calls from parents will be re-directed from profs to associate deans--which gives this prof another reason to believe that administrative bloat may not be all that bad.

Oh, and one note on Canadian/American cultural differences: after ultimate last night, I was asked about my trip last week that caused me to miss the last game, and I talked about college. The Canadians pointed out that college means something different up here--mostly technical or vocational schools. Even as most Americans who get BA's get them from universities (size matters), they refer to it as going to college. Which is strange given that American colleges range from junior to community to vocational to liberal arts colleges. Canada does not really have much in the way of liberal arts colleges (there are some near exceptions).

Monday, July 7, 2014

The Logic of Invidious Comparison: Political Science Edition

One of the books that most influenced me has been Donald Horowitz's Ethnic Groups in Conflict. He borrows heavily from social psychology to argue that ethnic group politics is heavily conditioned by social psychology. That individuals base their self-esteem on how their group is doing and how other groups are doing relative to their group. Denigrating other groups makes one's group and oneself seem better.

He calls this the logic of invidious comparison, and it helps to explain not just ethnic conflict within countries and conflict among countries but also less serious stuff like how much we end up caring about how well our sports teams do and how badly their rivals do.

Why do I raise this now? Because the website where aspiring and practicing political scientists can trade insults anonymously, Political Science Rumors, has become so obviously a place where Horowitz's logic (and that of the social psychologists he borrows from) applies so strongly. The general tendency is to focus on the rankings of schools and their performance on the job market--which means that people's egos and their incomes are potentially at stake if reputation matters so much more than the work.

Lately, the focus has shifted, perhaps because we are in between job markets (the poli sci job market starts to kick into gear in the fall with the first applications due in mid September and the first interviews taking place mostly in October and beyond), we now see heaps of posts taking shots at different subfields. People are trashing Political Theory, then they pile on International Relations and so on.

Given that most people are not that competitive beyond their subfield, why should they care about which journals matter to those in another subfield? If people get tenure in place x because there are many respected IR journals that count towards tenure, how does that matter to anyone else in another subfield? If these people at place x get denied tenure, it is very, very unlikely that the new job that might emerge from this denial would be in another subfield. So, there is no real rational reason to care so much about what each subfield tends to value, yet the subfield trashing goes on.

The logic of invidious comparison seems to make the most sense to me. One denigrates IR to make one feel better about one's own subfield and improves one's own self-esteem, and IR people denigrate other subfields to make themselves feel better.

Of course, making sense of anonymous posts is a waste of time, but it is my time to waste ;) Still, Horowitz's stuff gives me a good understanding of not just ethnic conflict, but the World Cup and posts by unnamed people. So, woot for Horowitz!

He calls this the logic of invidious comparison, and it helps to explain not just ethnic conflict within countries and conflict among countries but also less serious stuff like how much we end up caring about how well our sports teams do and how badly their rivals do.

Why do I raise this now? Because the website where aspiring and practicing political scientists can trade insults anonymously, Political Science Rumors, has become so obviously a place where Horowitz's logic (and that of the social psychologists he borrows from) applies so strongly. The general tendency is to focus on the rankings of schools and their performance on the job market--which means that people's egos and their incomes are potentially at stake if reputation matters so much more than the work.

Lately, the focus has shifted, perhaps because we are in between job markets (the poli sci job market starts to kick into gear in the fall with the first applications due in mid September and the first interviews taking place mostly in October and beyond), we now see heaps of posts taking shots at different subfields. People are trashing Political Theory, then they pile on International Relations and so on.

Given that most people are not that competitive beyond their subfield, why should they care about which journals matter to those in another subfield? If people get tenure in place x because there are many respected IR journals that count towards tenure, how does that matter to anyone else in another subfield? If these people at place x get denied tenure, it is very, very unlikely that the new job that might emerge from this denial would be in another subfield. So, there is no real rational reason to care so much about what each subfield tends to value, yet the subfield trashing goes on.

The logic of invidious comparison seems to make the most sense to me. One denigrates IR to make one feel better about one's own subfield and improves one's own self-esteem, and IR people denigrate other subfields to make themselves feel better.

Of course, making sense of anonymous posts is a waste of time, but it is my time to waste ;) Still, Horowitz's stuff gives me a good understanding of not just ethnic conflict, but the World Cup and posts by unnamed people. So, woot for Horowitz!

American Exceptionalism--the Good Kind

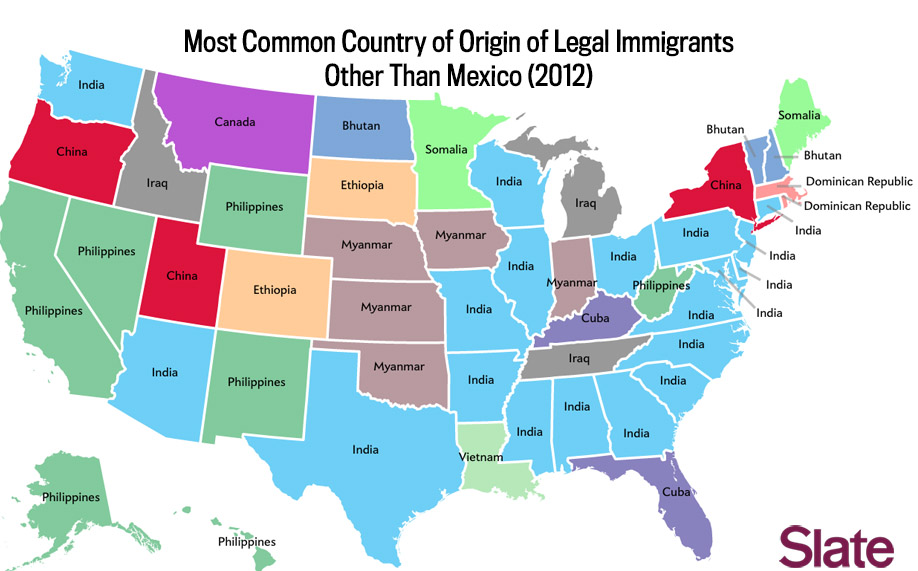

One of the big differences between the US and Europe seems to be that the flows of people into the US (and Canada) are far more diverse. This is best illustrated by the recent Slate map:

While the largest group immigrating into the US are Mexicans, we can see here that people from other parts of the world are immigrating. The non-India, non-China, non-Cuba immigrants may be somewhat surprising. The key here is that no one group really dominates the immigration picture. Sure, Sam Huntington's dead body would still point out that Mexicans are number one, but the new Americans are a diverse lot.

This is good for a number of reasons, but my point here is that it means that there is less of a sense by those already here that they are being swamped by one group with one set of values (as if any one group entirely shares the same set of values). Sure, I got a strange Mexican-ization question earlier this year about the forthcoming US Civil War II, but the reality is there is probably less antagonism and less strife when the newcomers are a mix. Which values will alter the existing American ones? Those based on Hinduism? Catholicism? Buddhism? The answer is none of the above.

Instead, my guess (as a non-expert on migration) is that the American stew will just have a few more spices, but will remain largely the same. Sure, there will be more non-whites compared to the whites, but more brown Americans is only a probably if you are ... racist. Sure, parties that pander to racists might suffer, but there is an answer to that--don't pander to racists. For all of Stephen Harper's problems, his brand of conservatives long ago figured out that playing to immigrant communities was good for their political chances. Democracy is kind of cool that way--if you want more votes, then appeal to those beyond your narrow group (if the lines and institutions are drawn the right way).

Anyhow, the real contrast is between the US and its European friends who are facing heaps of stress with their immigrant populations in part because of the relative size of the flows, in part because they are relatively new to the immigration game, and in part because the immigrants all seem to be part of one community.

One joy of the Furth of July is that the ideas behind the declaration, once one corrects for gender, apply so broadly--that all people are created equal, with rights to life, liberty and happiness (property sounds so crass). The American struggle is not with the ideals but how to implement them well. Because if we don't have cool rules ourselves, we will be bogus too, as the great political philosopher Jeff Spicoli instructed one score and twelve years ago.

|

| http://www.slate.com/articles/arts/culturebox/2014/05/immigration_map_what_are_the_biggest_immigrant_groups_in_your_state.html |

While the largest group immigrating into the US are Mexicans, we can see here that people from other parts of the world are immigrating. The non-India, non-China, non-Cuba immigrants may be somewhat surprising. The key here is that no one group really dominates the immigration picture. Sure, Sam Huntington's dead body would still point out that Mexicans are number one, but the new Americans are a diverse lot.

This is good for a number of reasons, but my point here is that it means that there is less of a sense by those already here that they are being swamped by one group with one set of values (as if any one group entirely shares the same set of values). Sure, I got a strange Mexican-ization question earlier this year about the forthcoming US Civil War II, but the reality is there is probably less antagonism and less strife when the newcomers are a mix. Which values will alter the existing American ones? Those based on Hinduism? Catholicism? Buddhism? The answer is none of the above.

Instead, my guess (as a non-expert on migration) is that the American stew will just have a few more spices, but will remain largely the same. Sure, there will be more non-whites compared to the whites, but more brown Americans is only a probably if you are ... racist. Sure, parties that pander to racists might suffer, but there is an answer to that--don't pander to racists. For all of Stephen Harper's problems, his brand of conservatives long ago figured out that playing to immigrant communities was good for their political chances. Democracy is kind of cool that way--if you want more votes, then appeal to those beyond your narrow group (if the lines and institutions are drawn the right way).

Anyhow, the real contrast is between the US and its European friends who are facing heaps of stress with their immigrant populations in part because of the relative size of the flows, in part because they are relatively new to the immigration game, and in part because the immigrants all seem to be part of one community.

One joy of the Furth of July is that the ideas behind the declaration, once one corrects for gender, apply so broadly--that all people are created equal, with rights to life, liberty and happiness (property sounds so crass). The American struggle is not with the ideals but how to implement them well. Because if we don't have cool rules ourselves, we will be bogus too, as the great political philosopher Jeff Spicoli instructed one score and twelve years ago.

Mitigating Risk, Public Relations Edition

In the course of many conversations with Canadian military officers for the NATO book and its successor (under review now), a frequent theme was risk. How to deal with uncertainty? In the past, the emphasis was on avoiding risks, but for a military to do that, it means staying at home or staying behind the wire. That is, not going out beyond the base.

Of course, that is deceptive because staying within a base does not eliminate risk either. It might mean having less situational awareness due to the lack of patrolling. It might mean not actually accomplishing the mission's objectives, so that the mission itself may fail.

The best example of this was that Bill Clinton told his generals not to lose any lives in Bosnia, which for much time meant that the US forces in IFOR and then SFOR did not follow up on some key tasks.... namely the pursuit of PIFWCs--persons indicted for war crimes. Chasing these folks down might lead to confrontations and perhaps even violence. So, the US at first did not pursue them. But this endangered the mission because the people of Bosnia perceived themselves to be at risk as long as the war criminals were free and also perceived the international community to be less than credible.

The new generation of Canadian officers focused less on avoiding risk and more on mitigating risk. That is, taking stock of the various possible challenges and then trying to deal with the potential dangers that may arise, focusing on most likely and then moving to less likely.

Why do I raise this now? Because I was struck by an interview with the head of the Canadian army today, Lt.General Marquis Hainse. I interviewed General Hainse a few years ago because he had served in Afghanistan in a key NATO post. His conversation with me then reflected much less risk mitigation than the interview in today's Citizen.

Asked about cuts to the budget, Hainse is clearly engaged in two sorts of risk mitigation exercises--how to reduce the army's budget without undermining its ability to do stuff; and how to talk about it without getting too much fire from the government. Regarding the former:

His risk mitigation when it comes to the government is played in another quote:

So, this interview reflects not just the effort by Hainse and his officers to manage the risks the army faces due to having less money but also the risks of talking about such stuff when the government prizes message management above all else.

Of course, that is deceptive because staying within a base does not eliminate risk either. It might mean having less situational awareness due to the lack of patrolling. It might mean not actually accomplishing the mission's objectives, so that the mission itself may fail.

The best example of this was that Bill Clinton told his generals not to lose any lives in Bosnia, which for much time meant that the US forces in IFOR and then SFOR did not follow up on some key tasks.... namely the pursuit of PIFWCs--persons indicted for war crimes. Chasing these folks down might lead to confrontations and perhaps even violence. So, the US at first did not pursue them. But this endangered the mission because the people of Bosnia perceived themselves to be at risk as long as the war criminals were free and also perceived the international community to be less than credible.

The new generation of Canadian officers focused less on avoiding risk and more on mitigating risk. That is, taking stock of the various possible challenges and then trying to deal with the potential dangers that may arise, focusing on most likely and then moving to less likely.

Why do I raise this now? Because I was struck by an interview with the head of the Canadian army today, Lt.General Marquis Hainse. I interviewed General Hainse a few years ago because he had served in Afghanistan in a key NATO post. His conversation with me then reflected much less risk mitigation than the interview in today's Citizen.

Asked about cuts to the budget, Hainse is clearly engaged in two sorts of risk mitigation exercises--how to reduce the army's budget without undermining its ability to do stuff; and how to talk about it without getting too much fire from the government. Regarding the former:

"it’s about managing the risks. We have an older fleet [of trucks], an aging fleet, that we couldn’t just keep up in terms of maintaining. So we made a decision. And for that period of time, we’re going to assume a bit of risk in taking off some of the burden of that maintenance. There are enough trucks around to be able to still do our part in reacting to a domestic operation."Note this suggests something about his focus and what might be riskier in this fiscal climate--international operations. As Hainse faces the tough decisions, he is probably factoring into his calculations the unlikelihood that the Canadian army will be deployed into a significant combat operation anytime in the near future.

His risk mitigation when it comes to the government is played in another quote:

Q. What do you think of the government’s requirement that the military not cut personnel to save money?This is a non-answer, I am sorry to say. The government has restricted the military from cutting the numbers of active and reservist personnel. The magic numbers are for symbolic purposes and are not based on what capabilities Canada needs. There has been no adjustment of the numbers after Canada ended its most significant combat operation since Korea. Canada needed a larger army during the war to sustain operations, but with no new operations in sight, the military could get smaller. This is what happens to most democratic militaries in peacetime. Take a look at the U.S., which is making significant cuts to its army and to the Marines now after increasing their size when the Americans were fighting two (plus) wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

A. It’s about capabilities. What is it that the army needs to have to be able to answer the need? And once we answer that question and we agree what capabilities we need, then the rest flows out of this.